St John’s

From a conventual church to a Co-Cathedral

A * B * Ċ * C * D * E * F *

Ġ * G * GĦ * H * Ħ * I * J * K *

L * M * N * O * P * Q * R * S *

T * U * V * W * X * Ż * Z *

The building of a conventual church

Around the time that the fortification walls of Valletta were being completed, the the knights of the Order of St. John, Malta’s autocratic rulers, endeavoured to erect buildings inside the new town that were important to the island’s administrators. Not too distant from the Grandmaster’s Palace, a conventual church was built to serve exclusively to the spiritual needs of the members of the Order. This edifice took about five years to complete (1573 – 1577). The church was built, both from the outside as well as from the interior in the austere Mannerist style. The architectural design was created by the Order’s military engineer, the Maltese Girolamo Cassar.

Inside this newly built conventual church, there were a number of chapels, many of which, came under the responsibility of the knights of the various ‘Tongues’ or ‘Langues’ of the Order. These multi-national knights eventually started to bury their brethren pertaining to their langue in their respective chapels. From 1608 onwards, the burials began to extend beyond the chapels and onto the central nave, thus turning the bleak stone pavement into a colourful mosaic of inlaid marble tombstones. In total, the interior of the church became populated by some 400 inlaid marble slabs, although not all have actual burials underneath them. Meanwhile, other knights of lesser rank were buried in the cemetery outside the church, next to the Oratory, on the side of Merchants Street, then known as Strada San Giacomo.

Its embellishment

The Grandmasters too had their tombstones erected in a more flamboyant manner. In the crypt of the church, located underneath the high altar, there were buried the first eleven of the Grandmasters who ruled Malta. Among the tombs there are those of L’Isle Adam, La Valette, and La Cassiere. The latter was the founder of the conventual church. It was he who had frayed many of the expenses necessary in its construction. Apart from these illustrious figures, a couple of centuries later, the same crypt received the corpse of Grandmaster Francisco Ximénes de Texada who died in 1775. More recently, in 2017, the late English Grandmaster Fra Matthew Festing was also interred there.

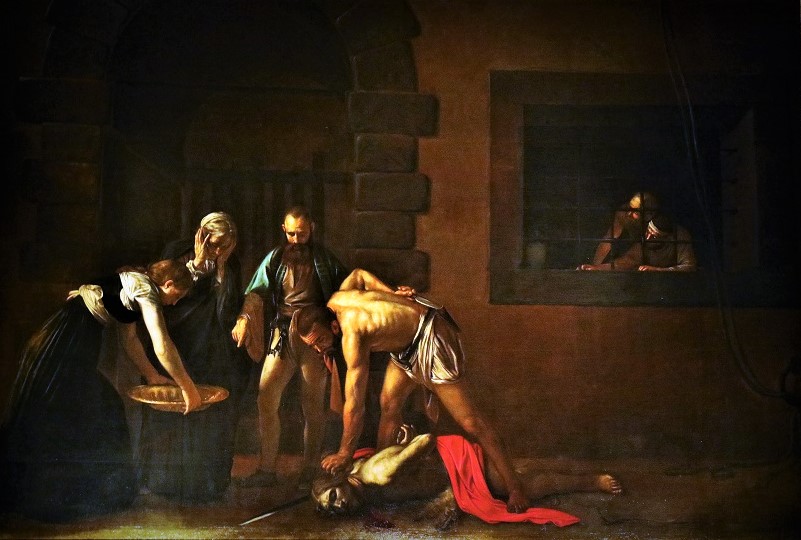

Adjacent and accessible from the conventual church, an oratory was built (1603 – 1605). When the renowned Italian artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio came to Malta in 1607, Grandmaster Alof de Wignacourt commissioned him to paint the large tableau ‘The Beheading of Saint John’ which he painted in situ behind the altar. Another painting by Caravaggio that presently is exhibited in the Oratory is ‘The St. Jerome’. This was originally commissioned by Fra Ippolito Malaspina as his own prestigious acquisition but the knight later bequeathed the painting to the Order’s conventual church to be hung in the chapel of Italy.

Mattia Preti – master of the Baroque

Eighty years had passed since the building of the church, when it was decided that this religious edifice should be given a more prestigious appearance – from a church built in a simple and humble architectural style Grand Master Raphael Cottoner now intended to upgrade the interior of the church to become a Baroque showpiece. The embellishment project was commissioned to the Calabrian artist Mattia Preti who started the work in 1660. The artist completed the project within six years.

Preti realised that if his artistic works were to be fully appreciated it was necessary to enlarge the windows on each side of the barrel vault, in order to allow in ample natural light. In this manner, amongst other things, he was able to make visible the series of episodes recounting the life of St John the Baptist which he depicted on the barrel vault. Preti initiated his work by first priming the white stone vault with linseed oil, instead of coating it with light white plaster as was usually the norm with frescoes. This he did as he relied on the naturally light coloured limestone that would immediately blend well with the colours applied to it. According to Preti’s concept, the side walls of the nave and those inside the chapels were profusely sculptured out in both low and high relief, to display a variety of symbols that related to the Order of St John and other relevant images. Eventually, all these designs were gilded over in gold leaves.

More works of art are added

Over time, each Grandmaster on being elected, would bestow the church with his own personal gift (known as gioia) to enhance the artistic prestige of this church. Arguably, one of the most beautiful gifts that were ever donated was the set of Flemish tapestries that Grandmaster Perellos y Rocaful bequeathed in 1702, following his election as Grandmaster in 1697. Contemporary to the tapestries is the statuary behind the main altar, depicting the ‘Baptism of Christ’ (1703). This is the work of Giuseppe Mazzuoli, an Italian artist who also was the only pupil of the Maltese sculptor Melchiore Gafa when the latter worked in his atelier in Rome. By the time the Order was expelled from Malta by the French in 1798, the conventual church had become not unlike an exhibition hall, flaunting all kinds of artistic works. The Order of St John wanted to show itself as having high artistic tastes, thus being at par with other civilised European rulers.

Symbolism of faith and power

Over time, many of the chapels inside the church were decorated with majestic monumental mausolea. Nicolas Cottoner’s mausoleum, located within the chapel of Aragon demonstrates the Order’s pretence of power and military superiority over its eternal enemy the Sultanate of Turkey with its Ottoman empire. In the same chapel the mausoleum of Grandmaster Perellos holds similar sway with the figures in marble that represent justice, generosity and power.

Malta’s Bishop is not allowed

Meanwhile, during the time that the Order ruled Malta, the Bishop was bereft of any claims of access to the church, which although a Catholic one, tried as much as possible to keep its distance from the bishop’s jurisdiction. The knights had their own chaplains to carry out all religious ceremonies to the exclusion of all other local Catholic dignitaries. Thus, in 1577, the same year when when St John’s had just been completed, the Cathedral Chapter of Mdina embarked on the building of another church in Valletta where the Bishop could officiate his own liturgical functions. This new church which was built just a stone’s throw away from St. John’s, and dedicated to Saint Paul’s Shipwreck, was never elevated to any specific title, and thus functioned mainly as one of the parish churches of Valletta.

Meantime, the Cathedral Chapter of Mdina still coveted the use of the Order’s conventual church of St John’s, so that when Napoleon expelled the Order from Malta, Bishop Vincenzo Labini immediately found it opportune to demand from the French authorities to start holding religious functions inside the ex-conventual church. This request was accepted by Napoleon on a temporary basis.

Claims of ownership during the British period

Once Britain took over the administration of Malta in 1800, Alexander Ball, the first Commissioner appointed to govern Malta and Bishop Labini immediately locked horns to engage over their claims to St John’s. Britain was adamant to retain its rights over this prestigious church which was regarded as having been transferred from one governing body to another. Bishop Labini and later on, Bishop Ferdinando Mattei maintained that the Order had administered St. John’s as a religious insitution, and that there had been an agreement that, were the Order to leave Malta, the church would be handed over to Malta’s bishopric. Notwithstanding these interpretations, the Maltese clergy defied any British imposition and continued to officiate inside St. John’s. On being elected Bishop in 1808, Ferdinando Mattei, picked up the cudgels and strove to reach an uncomfortable compromise by which the Cathedral Chapter would continue to make use of the church. However, Alexander Ball maintained his stance and insisted that a monarchical throne was to be set up on the presbytery of not only St. John’s but also inside the Mdina Cathedral. In so doing the British made it clear that they Labini

to override any pretensions of the Maltese Church and that the local clergy was to show total allegiance to the British Crown. Meantime, Mattei continued to debate the matter with the Vatican. He coaxed Pope Pius VII to elevate the church to the dignity of a Co-Cathedral, a title that ranked the status of St John’s at par with the Cathedral of Mdina. The Pope complied and on 20 January, 1816, St John’s was declared a Co-Cathedral. In so doing, any designs that the Protestant authorities had, to wrest the church from the Catholic authorities, were dashed. For the British this new title was of little consequence as long as the Governor retained the claims of property ownership over the church and any benefices endowed to it. On 8 November, 1822, Mattei once again approached the first Governor of Malta, Thomas Maitland, to formally concede to the Cathedral Chapter to make permanent use of the church. Maitland accepted this request, however, he never acceded to any property claims by the Maltese Church. Although such an agreement was not a clear cut victory for the Bishop of Malta, the situation warranted some advantages, in that, the Maltese ecclesiastic authorities now could, whenever the Co-Cathedral required any major restoration or maintenance works, turn to the British Governor to fray the expenses involved. (M. Buhagiar, 1991).

Claims of ownership raises its head in the 20th century

Needless to say, this status quo was bound to unleash trouble sooner or later. However, when such trouble occurred, it was not with the British Governor that the Curia clashed but with the Maltese Labour Government, in the later years of the 1950’s. In 1956, the Italian Government had offered to restore the two Caravaggio paintings, both ‘The Beheading of Saint John’ and ‘The Saint Jerome’. These two priceless pictures were taken to Rome where they were duly restored. Following the completion of restoration works, in February 1957, the paintings were sent back to Malta on the British naval ship HMS Striker. At the time the Labour Government was at loggerheads with the local Catholic Church over the issue of a possible political integration with Britain and the meddling of the Bishop over this matter. Thus, once the two famous paintings were unloaded from the ship onto the quay, the Labour Minister concerned, directed the handlers involved to transfer the pictures to the National Museum in Valletta instead of returning them to St John’s. This was done without any consultation with the Cathedral Chapter, on the pretext that inside the newly established National Museum, the pictures would be kept in a safer environment. (Mario Buhagiar 1991).

In truth, by his actions, the Government wanted to spite the Bishop and make it clear that the government had the right to excercise its authority about matters that pertained to St John’s Co-Cathedral and its treasures. This was the same argument that the British had used in the early decades of the 19th century. After a period of protracted wrangling, that even led to parliamentary debates between the political parties, common sense prevailed and the paintings were finally returned back to the Co-Cathedral on April 17, 1958.

Today, the St. John’s Co-Cathedral is administered by a Foundation set up to ensure the proper upkeep of the architectural and artistic heritage of St John’s while ensuring the sanctity of the place. The foundation operates and regulates also the daily admission of thousands of visitors who throng the Co-Cathedral to enjoy its artistic beauty. The same foundation is given the power to dispense of the funds accrued from entrance fees to the maintenance and restoration needs of St. John’s as required.

© Martin Morana

11 August 2023

Bibliography

- Arena Jessica, ‘Grand Master uncovered – Ximenes tomb finally found in Cathdral crypt’. Times of Malta, December 5 2021.

- Borg E.V. ‘The Splendour of St John’s Co-Cathedral’. Airmalta Inflight magazine.

- Buhagiar Mario, ‘The St. John’s Co-Cathedral Affair – A study of a dispute between Church and State in Malta over property Rights’, Melita Historica , Vol. X no 4, 1991.

- Cutajar Dominic, ‘The fabulous heritage of the church of St John’. Treasures of Malta. Vol 2, no.3, 1996.

- De Giorgio Cynthia, The Image of Triumph and the Knights of Malta. Printex Limited. 2003.

- De Giorgio Cynthia, ‘The Conventual church of the Knights of Malta’. Miranda Collection. Issue no 5. Progress Press Ltd.

- Farrugia Randon Philip, ‘Excellence and Elegance’. The Sunday Times, January 16, 2000.

- Mangion Giovanni, ‘The Magnificent pavement of St. John’s’. The Sunday Times, December 13, 1992.

- Freller Thomas, ‘Mattia Preti’s paintings for the vault of St John’s – some notes on the dates’. The Sunday Times, November 28, 1999.

- Grima Joseph F., ‘The arrival of the Flemish tapestries in Malta, 1702’. The Sunday Times, February 13, 2002.

- Mahoney Leonard, 5000 Years of Architecture in Malta. Valletta Publishing. 1996.

- Paulin Stefanie, ‘Ecclesiastical buildings of Gerolamo Cassar – 2’. The Sunday Time, January 21, 2001.

- Vella Theresa M. ‘The conservation project at St John’s: Problems and Solutions’. The Sunday Times, July 15, 2001.

- Zerafa M.J., Caravaggio Diaries. Grimand Company Limited. 2004.

- Die Co-Kathedrale von St John Valletta. MJ Publications. 1979.

Pubblikazzjonijiet tal-istess awtur – ikklikkja hawn: https://kliemustorja.com/informazzjoni-dwar-pubblikazzjonijiet-ohra-tal-istess-awtur/