A * B * Ċ * C * D * E * F *

Ġ * G * GĦ * H * Ħ * I * J * K *

L * M * N * O * P * Q * R * S *

T * U * V * W * X * Ż * Z *

The PHOENICIANS and MALTA

Cover photo: A painting by Jean-Pierre Houel (1787) of the so called Phoenician / Punic Tower in Żurrieq, Malta.

The origin of the Phoenician people

It is difficult to establish a specific year and land that proves the origin of the Phoenician people, distinct from other contemporary civilizations that lived close by. This because the Phoenicians lived in cities that were distant from each other and sometimes separated by a considerable terrain. Yet, the inhabitants of each town still bore many resemblances in their traditional way of life. According to many scholars, the Phoenicians were none other than the Canaanites mentioned in the Holy Scriptures. At around 1,200 B.C., a time when such tribes as the Philistines, the Israelites, the Arameans and the so called ‘Sea Peoples’ (the latter coming probably South East Europe and Anatolia) were merging in the Middle East. Eventually, the Phoenicians, were compelled to retreat towards the plains close to the coast of the Mediterranean, They consolidated their habitations into the cities such as Tyre, Sidon, Byblos, Acca, and Serepta among others; all located along the shores of Lebanon, Syria and parts of the Palestinian coast. Each of the Phoenician cities had its own political administration, independent from one another. At the time, the Phoenicians referred to themselves, as Kananites, from the Akkadian Kinakhnu. Likewise, the Egyptians referred to them with the same name.

The Phoenicians spoke a Semitic language, a dialect of sorts which was closely related to that of other Semitic tribes, such as the Aramaeans and the Israelites. Yet, the Phoenicians became identifiable with certainty as a distinct cultural group from those living around them at the time. They prove their peculiar characteristics in various ways, be it by their consonantal epigraphs, religious beliefs and rituals, as well as in the quality of the handicrafts they produced, such as pottery, ornamental works in gold, glass phials and the purple fabric that was traded in later centuries throughout the Mediterranean. On their pottery, the Phoenicians liked to draw ornate geometric designs, spirals as well as plants, especially palm leaves, and animals. They also produced decorative works in ivory. These artistic works were often inspired from other cultures such as that of Anatolia, Syria, Mesopotamia, but especially by Egyptian art. Ironically, most of the archaeological material that is attributed to the Phoenicians with certainty has not been discovered in their homeland but at archaeological sites all over the Mediterranean. In their travels, the Phoenicians mingled with many peoples thus influencing others, while absorbing a lot from these same cultures that morphed into their own artistic style.

It was the Phoenicians who, for the first time in history, invented a script that consisted of an alphabet unlike the pictograms of Egypt and others. This alphabet was made up of a quantity of characters each of which represented the sound of a particular consonant. The Greeks would later on add vowels to this alphabet.

Phoenician Trade

Around 1000 B.C., the Phoenicians began to sail away from their homeland, at first, to ply their ware, mainly with the inhabitants of Cyprus, where they bartered their purple cloth in return for copper ore (kúpros – was the name of Cyprus – meaning copper). The term, Phoinikes (Phoenicians), was given to them by the Greeks to refer to their purple cloth soaked in red dye that was made from a particular sea shell, the Murex trunculus. Indeed, at the time, the term Phoinikes did not refer to all the Phoenician people, but was a generic term that referred only to those merchants who traded in such cloth.

These traders eventually travelled further West where they established permanent commercial trading posts which in later years developed into colonies. By the eighth century B.C., the Phoenicians had already begun to extend their trade throughout the whole of the Mediterranean. They had established a presence in several foreign ports to trade in various handicrafts. It is said that the Phoenicians were not simply traders, they were also brokers or intermediaries in various trades, meaning that due to the great business they generated in other countries, they had their agents posted in many ports. Such permanent fixtures meant that eventually, these traders created settlements which were some distance away from the harbour towns. Thus began a gradual and peaceful ‘colonisation’ which does not reflect any sense of conquest and control over the natives, but simply the growth of a community that gradually settled away from home. This is quite a different concept from the colonisation that the Greeks established contemporaneously with their own authorian rule.

One of the ports that the Phoenicians settled in was Carthage (Kart Hadasht means, the New City) on the Tunisian coast. For generations, this Phoenician colony grew from strength to strength, eventually becoming a powerful administrative city state in its own right, and thus far more superior to all the cities of Phoenicia. Meanwhile, in 574 B.C., Tir, the most important Phoenician city, was destroyed by the Persians, while Carthage continued to flourish and even created its own satellite colonies such as Cadiz in Spain, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, Malta and Motya in Sicily.

Historians begin to refer to the Phoenicians of Carthage as well as their cultural influence on their established colonies in the Western Mediterranean, as ‘Punic’. Carthage became the new point of reference as from the beginning of the 5th century onwards, The distinction is an arbitrary one. Nevertheless, in later centuries the Romans also referred to the people of Carthaginians as ‘Punic’, a reference that still referred to those people who traded in red cloth.

The Phoenicians and Malta

The Phoenicians came into contact with Malta around the 8th century. It is not known why the Phoenicians stopped at Malta and eventually settled here. It is doubtful whether they came in contact with and traded with the last of the‘Bronze Age’ communities then inhabiting the archipelago. Malta did not have any raw materials to attract the trade interests of the Phoenicians and eventually barter for by their merchanise. Malta lies some 280 kilometres East of Carthage, therefore it could not have served as a main route when travelling from the Eastern coast of the Mediterranean along the North African littoral. However, Malta, located as it is, 93 kilometres South-eastern Sicily, then colonised by the Greeks, might well have offered an alternative port for the Phoenician traders to replenish themselves with provisions, when on their way to Western Sicily. Malta therefore became a logical haven when the Phoenicians travelled along the Northern Mediterranean littoral. At such stops, the Phoenicians might have needed to haul their vessels on land for emergency repairs or maintenance. For their service the local inhabitants would be paid in kind by merchandise that the Phoenicians plied all along the Mediterranean. From Malta, the route extended in a North-westerly direction towards the South-western tip of Sicily, where Marsala served as another port of call. From there they proceeded towards Sardinia, or else crossed the sea towards the North African coast to head for Carthage.

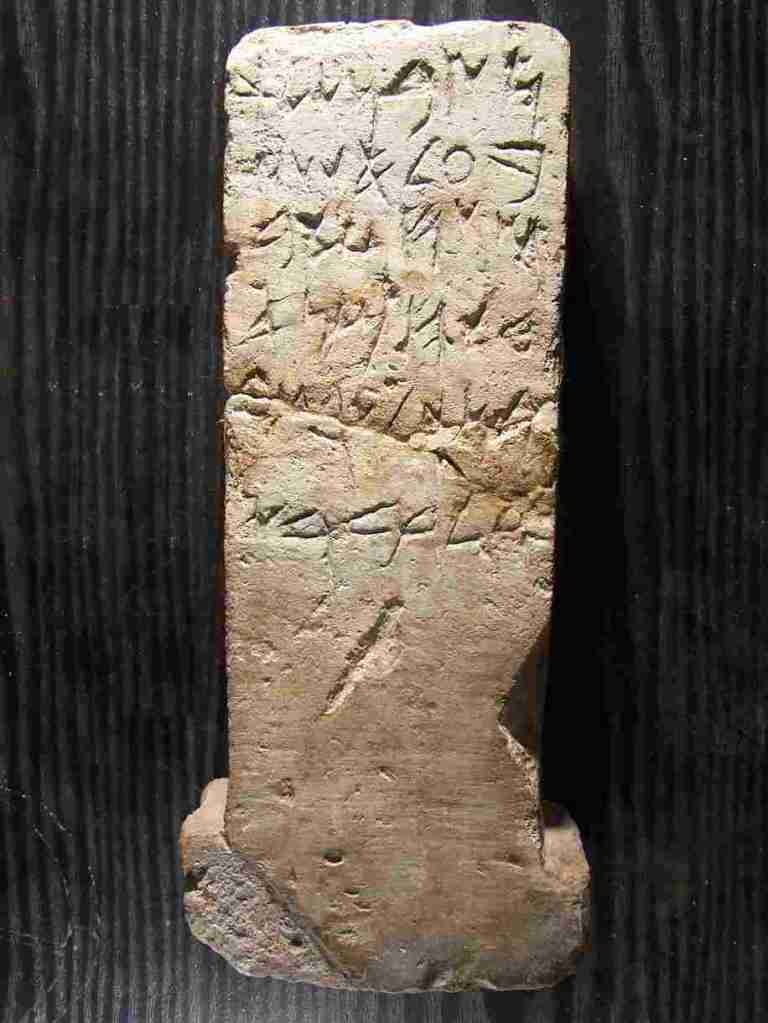

Phoenician remains in Malta

The oldest remains from the early Phoenician presence in Malta date back to the late eighth century B.C. It was at this time that the Phoenician temple at Tas-Silġ in Marsaxlokk was built, as they erected a shrine dedicated to the Phoenician goddess Ashtarte. Here the mariners who landed ashore visited the temple to make their offerings, a kind of an ex voto to thank the goddess for protecting them during their journey. The name of this goddess is found repeatedly inscribed on the votive pottery fragments. The earliest Phoenician temple at Tas-Silġ was constructed out of an earlier megalithic temple whose vestiges were still visible.

Apart from Tas-Silġ, other sites have yielded treasure troves of material from the 8th down to the 5th century B.C. During excavations in Mdina and Rabat Phoenician-Punic rock-cut tombs were brought to light. Such tombs are repeatedly discovered year in year out in numerous locations in Malta and Gozo give. They provide a good indication that some of these seafarers decided to make their stopover a permanent one and thus become one with the local communities present on the Maltese islands.

In Rabat, a clay sarcophagus was found in Ħal Barka. This coffin is made entirely of clay and is of an Egyptian-Rhodian style. A bowl with bird designs and a chalice was also found, which was probably the work of a Greek craftsman thus indicating contacts with the Hellenistic world. In some archaeological sites, Phoenician pottery that was glazed in red is thought to have been manufactured locally.

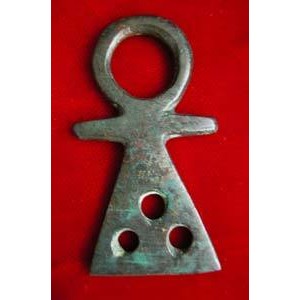

Numerous amulets were also found showing that the Phoenicians believed not only in their own gods, such as Melkart, Ba’al, and Ashtarte, but also in Egyptian deities such as Anubis, Horus, and Isis. These amulets were worn as talismans to protect themselves from danger, whether physical or spiritual. Amongst the talismanic amulets there were the ugiat (the eye symbol) and the ankh, the Egyptian symbols of life that is often seen in the hands of Egyptian pharaohs.

Was there a tofet in Malta?

As in Carthage and Motya, it seems that in Malta too, human sacrificial rituals were practised. This was a macabre custom known as the molk. It is believed, that the Phoenicians habitually sacrificed their first born child at the age of nine. Following the killing ritual, the corpse would be burnt as an offering to the Phoenician god Ba’al. The ritual place where this sacrifice was held is known as the tofet. Although in Malta there is no tangible proof that the molk sacrifice took place, and no tofet has ever been found, yet, in the Tal Virtù area, Rabat, there were found two stelae (tombstones) with inscriptions referring to such a ritual that had taken place at some time or other.

In 218 B.C., the Carthaginians lost Malta to the Romans. However, it seems that this landmark event was only a military and a political one, meaning that the cultural traditions of the ‘Punic-Maltese’ inhabitants persisted up to centuries later. The Punic inscriptions discovered on the two cippi (incense burners) in Marsaxlokk prove the fact that the Punic language was still spoken on the Maltese islands as late as the 2nd century A.D. On the same cippus the Punic inscription is copied in Greek. Interestingly enough, no Latin version was included.

—–

One final note about the Phoenician culture: Saint Augustine (354 – 430 AD) when he referred to the people the North Africa, he refers to them as Canaanites’.

© Martin Morana

25.08.2023

- Bibliography

- Bonanno Anthony, Malta, Phoenician, Punic, and Roman. Midsea Publications Ltd. 2005.

- Ciasca Antonia, ‘Le Isole Maltesi e il Mediterraneo Feniċio’, Malta Archaeological Review, Issue 3, 1999.

- Frendo Anthony, ‘Some Observations on the Investigation of the Phoenicians / Caananites in the Ancient Mediterranean World’. Journal of Mediterranean Studies, Vol 3. No 2. 1993.

- Frendo Anthony & Bonanno Anthony, ‘Excavations at Tas-Silġ’, Malta Archaeological Review, Issue no 2, 1997.

- Gonzalez Vidal, ‘Malta in Phoenician and Punic times’, Malta Archaeological Review, Issue 3, 1999.

- Gouder Tancred C., Accenni su Malta Fenicia’, Malta Archaeologicial Review. Issue no. 3, 1999.

- Masini Franco, ‘Gozo’s crown jewels’. The Sunday Times of Malta, December 16, 2001.

- Moscati Sabatino, I Fenici. Bompiani.

- Richardson Jim, ‘Carthage and Malta’, The Sunday Times of Malta, November 24, 1996. Lombard Bank. 1991.

- Saliba Elizabeth & Paul C., ‘Photographic representations of the Melitensia Quinta’. The Sunday Times of Malta, November 22, 1998.

- Zammit Rosanne, ‘Conservation Work at Tas-Silġ’, The Times of Malta, December 2, 2000.

- Zammit Ciantar Joe, ‘Notes on two Phoenician sarcophagi’, The Sunday Times of Malta, March 18, 2001.

A * B * Ċ * C * D * E * F *

Ġ * G * GĦ * H * Ħ * I * J * K *

L * M * N * O * P * Q * R * S *

T * U * V * W * X * Ż * Z *

PUBBLIKAZZJONIJIET TAL-ISTESS AWTUR

ikklikkja hawn …