MALTA DURING

THE GREAT WAR

(1914 – 1918)

All popular history books attribute the casus belli of the Great War to the assassination of Prinz Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary and his wife in Sarajevo, by a Serbian national. That may well have been the spark that blew the fuse to start the blazing battles. However, the war was truly the result of the belligerent stance taken by the Big Powers, that is Germany, France, Russia and Britain against their adversaries as each sought to outdo one another in military build and enhance their empire. To quote the famous author H.G. Wells (1866 – 1966), this was supposed to be ‘the war to end all wars’.

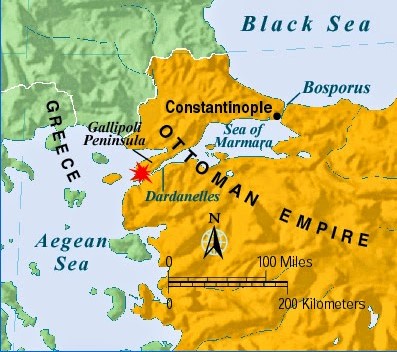

While the war gained momentum in Europe, in late October, Turkey took side with Germany as it aspired to regain some of its lost Empire in Eastern Europe. She also coveted Egypt and the Suez Canal. Thus Britain and France, thought fit to neutralize Turkey by landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula. This they did on April 25 1915, aided by Australian, New Zealanders, as well as by Canadian and Indian forces. However, there they were met with great resistance by a very tenacious Turkish army. For the following 9 months the Allies stalled, while each side inflicted huge human losses on one another. In order to sustain its campaign at Gallipoli, Britain had laid out plans to establish Malta, Cyprus and Egypt as her military bases, where from troops were dispatched to the battlefronts.

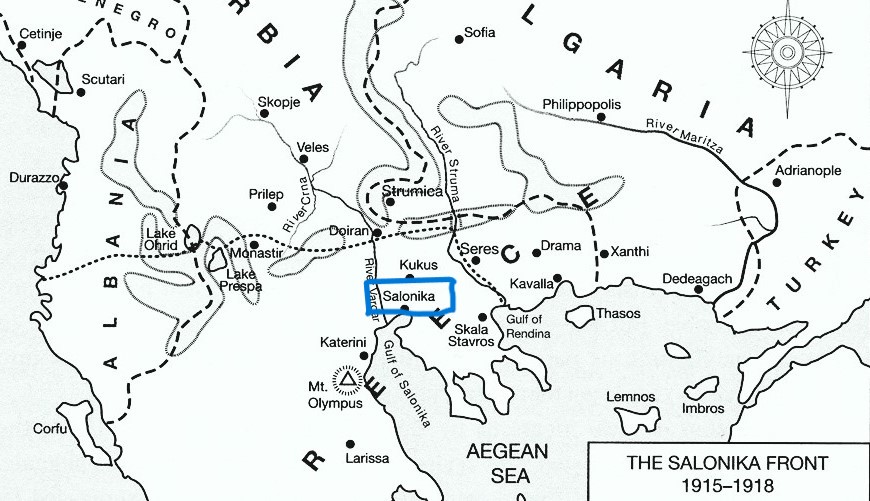

Then, on September 25 of the same year, a Franco-British army landed in Salonika, (better known today as Thessalonika) Greece, with the objective to help Serbia defend itself from German-Austrian and Bulgarian troops. Here too, the Allies were to suffer terrible losses, not only due to direct military action but also by contracting diseases such as malaria, typhoid and dysentery.

Malta as a military base for the Allies

As the war escalated further, some 800 Allies’ troop ships were calling at Malta’s ports each month. Some 150,000 tons of coal was bunkered weekly. It was agreed that the French Navy was to take care of matters in the Mediterranean and Churchill even invited the French admirals to use Malta ‘as if it were Toulon!’ Indeed, 40 French naval assets entered the Grand Harbour on August 11, 1914 (H. Ganado, 1977). From her side, Britain transferred newly developed seaplanes to Malta on board the H.M.S. Ark Royal. The planes were to escort Allies’ convoys, and to be on the look out for German submarines lurking in the central region of the Mediterranean Sea.

Maltese battalions and other auxiliaries

Throughout the Great War, more than 32,000 Maltese were involved in the war operations, 16,000 of them with the Admiralty. Thousands were employed as Dockyard workers, stevedores and other related activities. Another 15,000 were engaged with the British Military. On August 1, 1918, 770 men were recruited in the newly formed R.A.F. (J. Bonnici & M. Cassar, 2004).

On 15 January, 550 soldiers of the King’s Own Regiment of Militia were dispatched to Cyprus under the Maltese Lieutenant Colonel Charles Sciortino. In September of the same year, 1,100 members of the Malta Labour Corps were shipped to the Dardanelles. Later on, as the Allies diverted their attention to Greece, 1,300 men were dispatched to Salonika to provide logistical assistance. On December 5, 1917, another Maltese battalion was sent to Salonika. This was followed in February 1918, by other employment companies. (A. Laferla, 1977). Towards the beginning of the war, 650 Maltese volunteers also enlisted as auxiliaries with the Royal Navy, many as firemen (M. Galea, 2014). Some 300 others served with the Canadian and Australian forces (A. Zarb-Dimech, 2004). When H.M.S. Inflexible was hit on March 18, 1915, seventeen Dockyard workers who were carrying out repair on board, perished (J. Bonnici & M. Cassar). Many Maltese crew members were involved during the naval battle of Jutland (May 30 / June 1, 1916). Another ill-fated event occurred on January 20, 2018, when the H.M.S. Louvain was torpedoed in the Aegean Sea and 72 Maltese crew members went down with the ship (A. Zarb-Dimech). Mine sweeping was also regularly entrusted to Maltese crew.

Malta as ‘Nurse of the Mediterranean‘

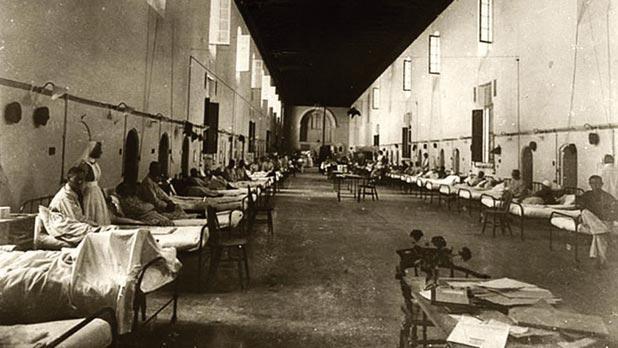

Once the invasion of Gallipoli was proving a hard nut to crack, the British realised that the hospital beds in Egypt and Cyprus would not be able to cope. Good thing that in March of 1915, a number of schools, military barracks and other spacious buildings were taken over to be converted into hospitals. In the span of a few months, the number of hospital beds available reached some 20,000. These were spread in 28 new hospitals (A. Zarb-Dimech). Later on, hospital camps, such as the one at Għajn Tuffieħa were set up. In January 1916, some 330 doctors, 900 nurses and a medical corps of some 2,000 were sent over to Malta from the United Kingdom to take charge. Twenty seven Maltese doctors joined the team (J. Bonnici & M. Cassar). When the hospitals reached full capacity, many Maltese nurses volunteered their services in their time off (A. Laferla).

The first of those injured in Gallipoli landed in Malta on 4 May, 2015. Some 600 soldiers were brought to shore, at Customs House landing Quay. These were followed a few days later by another 800 (A. Zarb-Dimech). A procession consisting of motor vehicles and horse-drawn ambulances carrying the injured would wind its way up Crucifix Hill in Floriana to reach Valletta’s Porta Reale in a few minutes. From here they were conveyed to the Military Hospital, locaterd close by to another old hospital, the Sacra Infermeria (formerly the hospital of the Order of St John). While being conveyed in their ambulances the injured were greeted by hundreds of curious Maltese who had lined up on the pavements to watch the spectacle. Many handed boxes of chocolate, packets of cigarettes, and flowers to those patients lying in open ambulances (H. Ganado). Once at the Military Hospital, the wounded were either tended to thereat, or else, were assigned to a different hospital according to their injuries.

The Valletta and the Birgu Hospitals were assigned the most serious cases. The Ħamrun hospital was reserved for those with eye injuries. Bighi Hospital took the naval casualties. The Mtarfa hospital was to receive those with infectious diseases (M. Bishop, 2002). The less serious cases were dealt with at Tigné Barracks at Sliema Point. Others were to be provided with a passage back home for further treatment. By the end of May, some 4,000 cases were being treated in eight hospitals. By September, the number rose to 10,000. It is believed that throughout the war, the Malta hospitals were to receive a total of 80,000 casualties. (A. Laferla).

Various voluntary institutions, such as the British section of the Red Cross were also involved in taking care of the patients. These organisations opened numerous facilities across the islands where those recuperating would not remain idle. Tea and game rooms were set up and they even engaged an orchestra for the enjoyment of all. Local Festa bands were also engaged to play in the grounds of similar recuperation facilities. One such entertainment hall was opened at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Scots Church in Valletta. Here some 400 to 500 soldiers frequented the place daily. (M. Bishop, 2002).

The local clergy also showed itself sensitive towards the ailing patients. The Bishop of Malta, Maurus Caruana, bade the local parish priests, to keep the ringing of church bells to a minimum so as not to deprive the patients in nearby hospitals of their needed rest. He also ordered that funeral services and prayers dedicated to the dead be held in all churches. The Bishop even offered his own official residence in Mdina to be made use of by convalescents. (M. Galea, 2014).

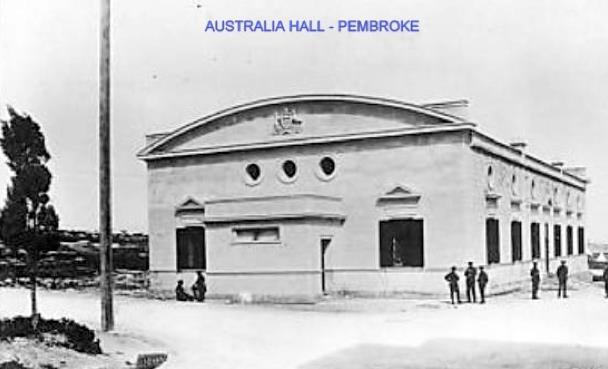

In January of 1916 Australia Hall was inaugurated at St Andrews, for the benefit of the Australian and New Zealand soldiers. The large hall could accommodate 100 tea tables and six billiard tables. Whenever a stage show was held, the place provided seating for 2000. The Union Club in Sliema also opened its doors to welcome recuperating patients to while away some time at the premises. Those patients who were not bed-ridden were offered sea trips to St Paul’s Bay on motor launches. Maltese families, who owned a car, volunteered to take convalescents for a drive or else invite them home for tea (J. Bonnici & M. Cassar).

The Dockyard – all hands on deck

In 1914, due to so many ships calling at Malta for repairs, the Dockyard had increased its labour force from its hitherto 5,000 to some 15,000 workers (M. A. Sant, 1989). More than just repair work was conducted at the Dockyard. At one time, 25 sea planes were assembled there by the workforce (A. Zarb-Dimech). This project however, left a bitter taste amongst the Dockyard workers when, on completion, those involved were awarded a 10 percent bonus. This was regarded as a mere pittance and the workers protested vehemently. Some 4,000 of them had by then already joined the Malta Government Workers Union. Consequently, on 17 May, the Union ordered a strike in which some 10,000 workers took part, demanding a raise in salary. The port stevedores also went on sympathy strike.

Another out of the ordinary task at the Dockyard was started in August of 1915. This was the assemblage of hand grenades. Indeed, some 68,000 grenades were manufactured locally and expedited to the war zones. The grenades were first manufactured in shell form at a Ħamrun foundry, then sent to the Naval Ordnance Department at the Dockyard, each to be fully assembled with gun cotton, a brass-plug and a time-fuse. This last phase of the production was assigned to soldiers of the Royal Malta Artillery. On October 5, tragedy struck, when a stack of some 100 grenades accidentally blew up. Fourteen men died and 15 others were injured (A. Zarb-Dimech).

Effects of the war on the Maltese Economy

Although Malta suffered no direct aggression by enemy action, yet, the war took its toll on the population in various ways. Sure enough, because of the war operations, unemployment was at an all-time low, yet the wages were meagre while the price of food and fuel kept rising. The price of bread rose from the pre-war price of 2½ pence to 6 ¾ pence; sugar from 3 pence to 1 shilling t’pence; meat from 1 shilling to 3 shillings six pence. To mitigate matters, the government was subsidizing the millers by some £2000 a week thus keeping the price of bread to a minimum (A. Laferla). The situation grew worse when on February 1, 1917, Germany declared ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’. Meat and wheat had to be imported for the first time from as far away as Australia. Because of the risk imposed by German submarines, no more injured were being sent to Malta for fear of hospital-ships being torpedoed, and so the local hospitals started to close down and Maltese aid workers were dismissed.

The local political scene

As from the start of the war, the Administrative Council headed by Governor Lord Metheun, enforced a very strict martial law on the Maltese islands. Censorship on all matters was strictly in force. Any political aspirations for a liberal constitution were thrown to the dogs. Moreover, no dissent related to government policies was tolerated. The Executive Council of Government was completely submissive to the decisions of the Governor.

A new entrant into the political arena was Enrico Mizzi who took up the cudgel of his father Fortunato, for a closer affiliation of Malta to Italy. Indeed he went as far as to declare publicly that Malta’s future should be with Italy. In April 1917, during a debate, Mizzi chastised the British administration in Malta, as being despotic. On 7 May, an irate Governor Metheun ordered the Police to raid Mizzi’s home to search for two articles he had published in the Italian press that proved to be subversive in tone towards British rule. Mizzi was arrested and court-martialled and found guilty. He was condemned to a one year jail term with hard labour. His sentence was soon commuted to a mere severe reprimand. Yet Mizzi was forced to step down from Government Council.

Earlier on, another figure who had been shadowing the political scene suffered worse. This was Manwel Dimech, a self-taught liberal, a socialist and an anti-cleric who for years had been fighting his own personal battle against the ruling class. He continuously urged the Maltese to ‘wake up from their political slumber’, and to stand up and fight for their rights. At the onset of the Great War, the British Governor saw Dimech as an upstart who had to be taken off the streets. Fearing that this man could cause popular agitation against the government, Lord Metheun had him arrested and exiled from Malta, to Sicily, and from there transferred to Alexandria in Egypt. Even after the war came to an end, Dimech was not allowed to return home and he eventually died in Alexandria 1921.

Prisoners of War held in Malta

Captured enemy sailors were interned at Salvatore Fort, located just outside Birgu. High ranking officers were interned at Verdala Barracks and the rest in camps, in the parade grounds of San Clement, close by. The prison population was composed of a motley of German, Austrian, Bulgarian, Turkish and Greek prisoners. At one point the prison population reached a total of 1,670. (A. Zarb-Dimech).

Two of the more prominent prisoners kept there were, Prince Franz Joseph Hohenzollern, a cousin of Kaiser Wilhelm, who was brought captive, together with 184 crew from the SMS Emden, and Karl Doenitz, Commander of the submarine, UB 68. The latter gained further notoriety during the Second World War, first as Sea Lord of the German Navy and later as Germany’s short term political leader, following Hitler’s demise.

Epilogue

Instead of bringing honour and glory, the Great War brought death and misery to millions. To a lesser extent, the Maltese too suffered death and deprivation. Some 600 who had provided their service overseas with the British Army and Navy never made it back to their families. Locally, many had to endure martial law, rationed food and hunger. As a major collateral damage, Malta and the rest of the world suffer disease and death caused by the ‘Spanish flu’.

Not all those injured or sick at Gallipoli or Salonika who were brought to Malta survived the ordeal. Others were already dead when brought to Malta. Maltese cemeteries, such as those at Pietà and Kalkara, were to receive the bodies of 1,542 British soldiers, 204 Australians and 73 New Zealanders (J. Mizzi, 1991). Some of the soldiers were buried three in one grave (M. Bishop). At the Kalkara Cemetery there were also buried 68 Japanese seamen. These died when their ship Sakaki was torpedoed in Crete. Japan had sent a naval force to the Mediterranean in March 1917.

WORLD WAR ONE – SOME SIGNIFICANT DATES

1914 June 28, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife are assassinated in Sarajevo.

1914, July 14, Russia starts to mobilise for war to defend Serbia

1914 July 28, Austria-Hungary, backed by Germany declares war on Serbia.

1914 August 1, Germany declares war on Russia.

1914 August 3, German troops invade Belgium in order to invade France.

1914 August 4, Britain declares war on Germany.

1914 October 28, Turkey enters the war on the side of the Central Powers.

1915 May 23, Italy joins the Allies of the Entente.

1915 April 25, British French Australian, New Zealanders forces land at Gallipoli.

1915 October 5, Landing of British and French troops at Salonika.

1917 April 4, USA declares war on Germany.

1918 November 11, Armistice Day.

© Martin Morana

7 August 2024

Bibliography

Attard Robert, ‘Memorabilia of the Great War’, Treasures of Malta, Vol. VII, no 3, Summer 2001.

Bishop Moira, ‘Nurse of the Mediterranean – The Scottish Connection during the Gallipoli Campaign’, Treasures of Malta, Vol. IX, No. 1, Christmas 2002.

Boffa Charles J., ‘Malta, 1917 – sinking of the hospital ship Gurkha’, The Sunday Times, May 9, 1999.

Bonello Giovanni, Malta and the French Navy.The Sunday Times, October 26. 2003.

Bonello Giovanni, ‘Malta-based Japanese warships contributed to Allied war effort’. The Sunday Times, June 22, 2003.

Bonniċi Joseph & Cassar Michael, A Chronicle of Twentieth Century Malta, Book Distributors Limited. 2004.

Camilleri Matthew, ‘Anzac Day Malta – Gallipoli Connection’ The Malta Independent, April 25, 2021.

Galea Michael, ‘Malta and its protagonists during World War I’. The Sunday Times of Malta, November 9, 2014.

Galea Michael, ‘Malta earns the title, ‘Nurse of the Mediterranean’. The Sunday Times of Malta, November 16, 2014.

Ganado Herbert, Rajt Malta Tinbidel – L-Ewwel Ktieb. Veritas Press. 1979.

Laferla Albert, British Malta, Vol. II. A. C. Aquilina & Co. 1978.

Mizzi John, Gallipoli – The Malta Connection. BDL. 1991.

Mizzi John, ‘Remembering Gallipoli’. Times of Malta. April 25, 2011.

Richards Denis, An Illustrated History of Modern Europe 1798 – 1974. Longman Group Ltd. London. 1977.

Sant Michael A., ‘Sette Giugno’ 1919 – Tqanqil u Tibdil. Sensiela Kotba Soċjalisti. 1989.

Zarb-Dimech Anthony, Malta During World War I. Veritas Press. 2004.

You may be interested to know more about other Maltese historical and cultural topics published by same author by clicking here…