COUNT ROGER

in Southern Italy, Sicily

& Malta

Early life

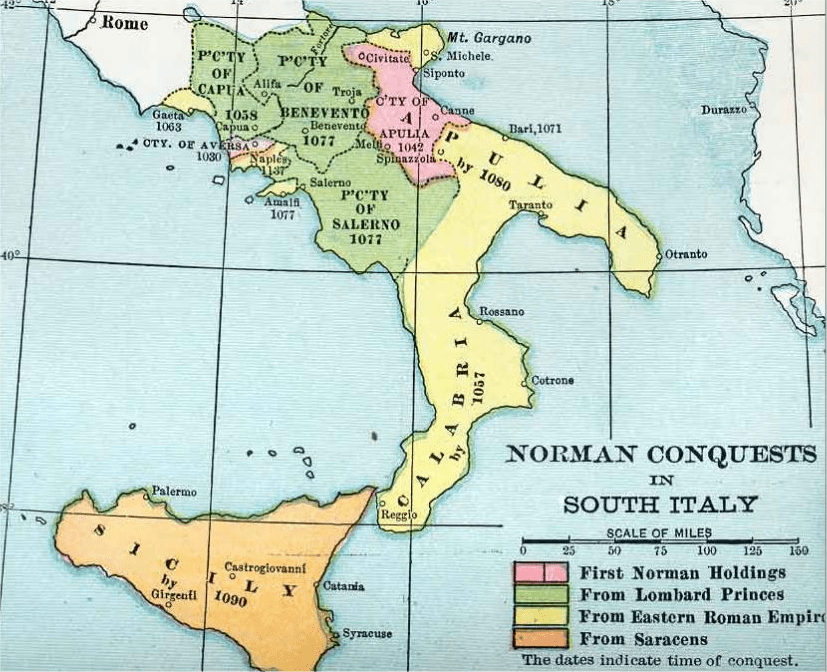

Roger of Hauteville was born in Normandy in 1031, the youngest son of Tancred de Hauteville and his wife Fressenda. Little is known about his early life and that of his brothers before the expeditions they led to Southern Italy. His travel to Italy in 1055, together with his brother Robert Guiscard, was caused by the ongoing military campaigns of their half brother Humphrey (Umfredo), Count of Apulia as the latter battled the army of Pope Leo IX, to grasp more of the papal territories (F. P. Tocco, 2017).

Arrival in Italy and conquest of Calabria

Roger, then a young man of 26, accompanied his brother, Robert Guiscard in his military campaigns. After a long siege, they conquered Reggio, the only city in Calabria still under Greco-Roman control. Here Robert was honoured with the title of Duke by his own troops and was later confirmed as such by Pope Nicholas II. Roger became his vassal of sorts and for a time, he lived in his castle of Scalea, near Cosenza. Roger later established his court at Mileto, a town located in the centre of Calabria, between Catanzaro and Reggio. From the fortresses of Reggio, the two brothers started planning the conquest of Sicily, which, since 840 A.D., was ruled by the Tunisian Muslims. Sicily, at the time, was also inhabited by a multitude of Greek Christians as well as Jewish communities.

The Invastion of Sicily

The idea to invade Sicily most probably came to fruition when Ibn al-Thumnah, emir of Syracuse, sought the Norman warriors’ military assistance to oust his brother-in-law, Ibn al-Hawwas, from Enna. Following his attack on Catania, Ibn al Thumnah sped first to Mileto to plead with Roger and then to Reggio to seek the help of Robert Guiscard. He promised both to make them his masters and that of all of Sicily.

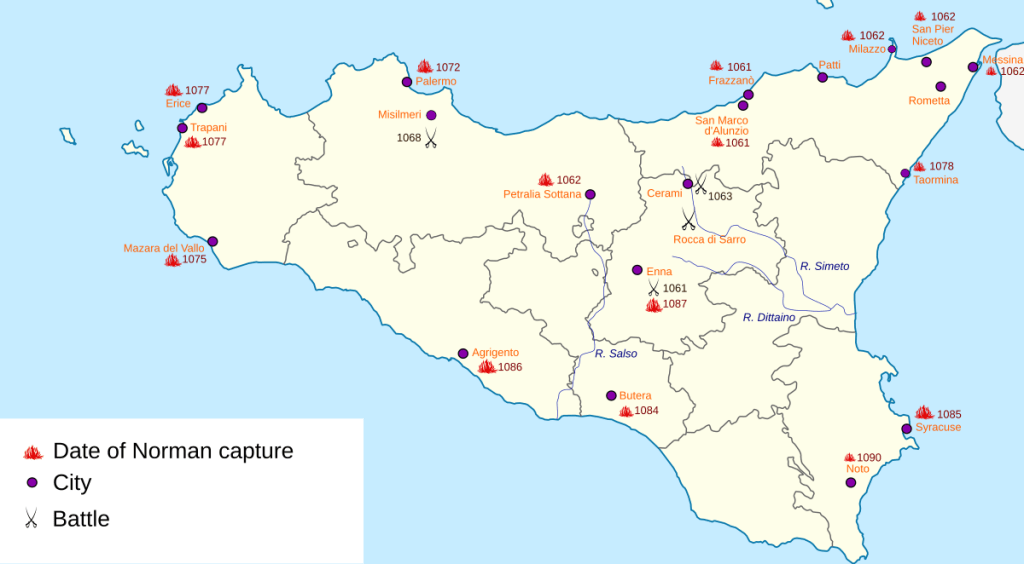

Thus, in November of 1061, Roger landed in Messina with his army, advancing mostly undisturbed, all the way to Enna. Unable to take Enna, perched as it is, some 935 metres atop high terrain, in 1063, Roger established his residence in Troina, a town located almost half way between Enna and Messina, to be able to control the roads crossing the central parts of Sicily.

In 1604, Roger and Robert attempted to take Palermo, the capital of Muslim Sicily, but failed. Diverting their attention to numerous other regions of Sicily, Roger and Robert were successful in capturing various other towns, while Palermo stood its ground for the next five years. In 1069 the Normans once again attacked Palermo but the city dwellers were able to resist this attack. In 1071, Roger and Robert laid siege to the city and after five months, on January 10 of 1072, they were successful in breaching the walls of the capital.

This victory over the rulers of Palermo ended the unitary Sicilian Muslim state as all the qaids in the Sicilian towns were obliged to pay their tributes to the qaid of the capital. However, in no way were the Normans as yet, in command of all of Sicily. It would take 21 years for the them to take complete control of the whole island, and a further 200 years for the various religious communities to come together and convenrt to the Latin-Christian religion. (Leonard C. Chiarelli, 2010).

Following the fall of Palermo, Robert Guiscard conferred the title of Count of Sicily to Roger, although Robert retained the territories surrounding Messina (Valdemone and San Marco) under his control. When Robert died in 1085, Roger, returned to Apulia to settle disputes between Robert’s two sons over their father’s inheritance. As it turned out, Roger was to take over the regions of Apulia and Calabria.

In 1077, Count Roger built a fleet to be able to gain a quicker access of all of Sicily’s peripheral towns by sea rather than by land. At this time Roger was aided by his son Jordan. In 1079, Taormina fell to the Normans and in 1086 Agrigento was similarly defeated. Roger then went to war with the emir of Syracuse and Noto. The Norman army laid siege on Syracuse and the town eventually surrendered because the population had run out of provisions.

After Syracuse, in 1087, Enna also ceded victory to the Normans. Another siege was laid on the town of Butera in Caltanisetta, in 1089. After this town fell to the military might of the Normans, in 1090, the Muslim leaders of Noto sued for peace. Thus, by 1091, Roger was in total control all of Sicily.

Count Roger – Ruler of Sicily

Over time, Roger’s rule in Sicily became more absolute, albeit also pragmatic. The mixed Norman, French and Italian vassals all owed their benefices to Count Roger. In addition, due to immigration by Lombards from the north and the installation of more Norman soldiers, Latin Christianity gradually gained ground, firstly in the Norman garrison towns.

In 1083, Count Roger took it upon himself to elect a bishop of Palermo, thus establishing the first diocese in Sicily. Within two years, he also appointed by his own right other bishops in Agrigento, Syracuse, Catania and Mazara. The chosen prelates were all Benedictine monks who had administered their religious communities in Calabria. Notwithstanding this Latinisation of Christianity all over Sicily, Count Roger upheld general toleration towards Muslims and Orthodox Greeks, even sponsoring the construction of over twelve Greek monasteries in the Valdemone region. In the cities, the Muslims, retained their mosques, their Qaids and freedom of trade. Not so in the countryside; here the Muslims became serfs. During Roger’s lifetime, no noteworthy uprisings occurred. Indeed, it is believed that he obtained a large supply of military men from the Muslim communities.

In Rome, Pope Urban II, was pleased to note that Roger’s handling of such religious conversions were propagating more members into the Roman Catholic Church. Nevertheless, in 1085, the Pope travelled to Sicily to meet with Count Roger in Troina to discuss issues related to the election of bishops, such as the latest one in Troina. During the talks that ensued, the Pope chose to concede and accept all appointments that Count Roger had previously confirmed. Nevertheless, when Pope Urban II decided in 1098, to establish his own bishop in Messina, Roger had the bishop arrested. Such was the absolute power of Count Roger in Sicily and in the South of Italy.

Count Roger died on 22 of June 1101 at the age of 70, in Mileto and was buried at the Benedictine Abbey of Santa Trinità in the same town. Upon Roger’s death, his child from his third wife Adelaide del Vasto, Simon, became Count of Sicily, with his mother acting as regent. Simon died at the young age of 12, (1105), and the title of count passed to his younger brother, Roger II (later to become King Roger). Once again his mother Adelaide continued to back Roger as regent.

The conquest of Malta

Already, in 1071, while Count Roger was occupied with the taking of Palermo, he made it known that he planned to attack the Maltese islands. This he would do, however, 20 years later, after the more hard pressing military campaigns of numerous towns in Sicily would come to a successful conclusion. Malta must have preoccupied Roger, lest the Arab rulers of Tunisia were to use Malta as a haven and a forward station for their maritime forces, and invade Sicily from the south eastern tip. It was only following the last showdown with the Arabs in Noto, in February of 1090, that Count Roger was ready to unleash his attack on Malta. For this venture he had built a new fleet to transport his troops across the Sicilian Channel. To lead this armada, Roger brought with him a small entourage of 13 knights to accompany him on horseback (Charles Dalli, 2006).

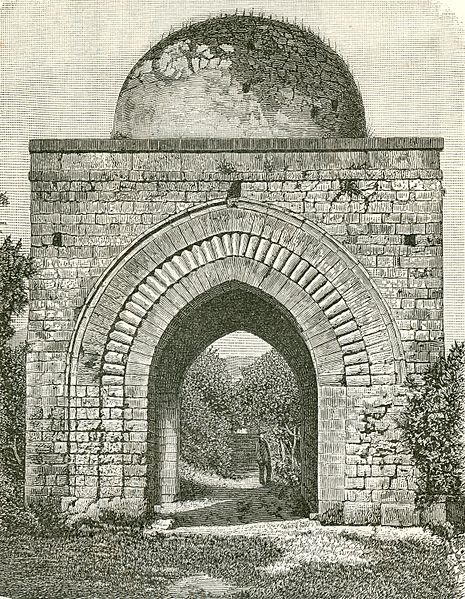

The attack on Malta was chronicled by the French Benedictine monk Goeffroi (Goffredo) Malaterra. On arrival, Count Roger met with some mild resistance when about to land. Soon his army reached the fortified town of Mdina, seat of the Muslim qadi who was the absolute leader of the local population of the Maltese islands, then amounting to a mere 10,000 souls. The qadi, was very much intimidated by the Norman’s siege engines, and so decided that instead of fighting off the Normans he would sue for peace (Charles Dalli, ibid.) The local leaders were obliged to acknowledge Count Roger as their overlord, while pledging their allegiance to him and paying an annual tribute.

The qadi also offered Count Roger to free all foreign Christians, captives who were serving their Muslim masters. These boarded Count Roger’s ships and were taken to Sicily from where they dispersed to their respective homeland. Following Roger’s entry into Mdina, the count and his army sailed to nearby Gozo. There too, Count Roger met with some resistance and so the Normans took to plundering all that was to be taken.

Nothwithstanding these two days of turbulence in the Maltese islands, it is generally believed that following Count Roger’s departure, very few things changed insofar as local administration and way of life. For years to come, the qadi still retained his authority over the local population which remained Muslim. (Anthony Luttrell, 1975, and Charles Dalli, 2006).

Thirty six years later, that is, in 1127, long after Count Roger had died, the Count’s son, Roger II, invaded Malta, most probably to break down some sort of resistance. It is believed that this time round, Roger II left behind a garrison and established a Norman style of administration on the island.

Legends that prevail about Count Roger’s invasion of Malta

About the invasion of Malta by Count Roger and its aftermath, many anecdotes were told as if they were authentic historical facts. Many historians interpreted Malaterra’s accounts the way they thought would be fit to prove that Christianity had survived the Arab dominion and that Count Roger was able to help the Maltese get rid of their Muslim rulers. These narratives written down by the early Maltese historians have been investigated by more recent scholars who reread Malaterra’s account and found to have no authenticity. Thus they are today relegated to the realm of ‘pseudo history’, or legends if you like. Below is a short list of some of these false claims that persist amongst many.

- It was widely claimed that Count Roger landed with his army at Miġra l-Ferħa, this being a precipitous location on the southern coast of Malta. This supposition is totally unfounded and very illogical as there is no way that an armada could climb its way up the steep cliff edge that rises some 100 metres from the sea. This anecdote was drawn simply from a misinterpretation of the Maltese toponym ‘Miġra l-Ferħa’ as meaning literally ‘the welcoming place’, or something similar, when in reality the miġra l-ferħa means and refers to a small watercourse.

- According to some historians, when Count Roger landed in Malta he liberated the Maltese nation from the Muslim-Arab rulers. When Goeffroi Malaterra tells that Count Roger liberated the ‘Christians’ from serfdom, he was not referring to the Maltese inhabitants but to Christian slaves, that is, foreign captives labouring for their Muslim masters. Indeed, it may well be assumed that during the Arab period, most if not all of the population of Malta adhered to the Muslim faith.

- Another anecdote maintains that Count Roger bestowed elements of the colours of his banner (red and white) to the Maltese people so that they would adopt these as their national flag. This could not possibly be true as at the time, no kingdom or feudal vassals, Malta included, sported their own national flag. The colours of the Maltese flag were established many centuries later, and apparently derived from the colours of the coat of arms of the town council of Mdina.

- Many historians wrongly claim that Count Roger rebuilt the cathedral in Mdina and re-established Christianity in Malta, even appointing a bishop. More so, it was widely believed that the parish church of Birgu was also founded by him. None of this is true.

- Another ‘wishful’ historical snippet that made the rounds was that Count Roger had a castle built in Mdina and another castle built at the tip of the Birgu peninsula.

- Apart from the above it was also believed that the last of the Muslim leaders were deported by Roger II in 1127. This did not happen. It was Frederick II, the Hohenstaufen Emperor, who ruled Malta from Palermo, who did this, some 125 years later.

Many of these stories have been given a romantic slant by early and not so early historians. One may say that down the centuries, Count Roger, known to the Maltese as il-Konti Ruġġieru, was interpreted by historians, as a pious heroic figure, a redeemer of the Christian faith which had been suppressed by the Muslim rulers throughout their rule. This interpretation was accepted by one and all, even by the local Catholic Church. So much so that the cathedral chapter commissioned the artist Stefano Erardi to paint the figure of Count Roger on horseback placed in the local context. This picture today may be seen in the cathedral’s sacristy. More so, at the same cathedral, each year, on November 4, a funerary mass used to be said to supplicate for the soul of Count Roger (Bjaġju Galea, 1975).

Martin Morana ©

March 5, 2025

Bibliography

Chiarelli Leonard C., Muslim Sicily. Midsea Books, 2010

Dalli Charles, Malta – The Mediaeval Millenium. 2006.

Dalli Charles, ‘Siculo Ingenio – Afro Confuso – Malta in the Late Middle Ages’, Malta – Roots of a Nation, Ed. Kenneth Gambin. Heritage Malta. 2004.

Fiorini Stanley, ‘The Gozitan milieu during the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Times’. Gozo and Its Culture, Ed. Lino Briguglio & Joseph Bezzina. Formatek Ltd. / University of Malta Gozo Centre. 1995.

Galea Bjaġju, L-Imdina ta’ Tfuliti. Klabb Kotba Maltin, 1975.

Luttrell Anthony T., Approaches to Medieval Malta. 1975. The British School at Rome. London. 1975.

Tocco Francesco Paolo, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 89. (Treccani, 2017).

Wettinger Godfrey, ‘The Norman Heritage of Malta’. Treasures of Malta, 1, 1995, 3.

For further reading of articles by same author … as well as info on pubblications, please click here: