ROMAN MALTA

(218 B.C. – A.D. 535)

A multicultural archipelago

Introduction

According to the Roman historian Livius (Titus Livius 59 B.C. – A.D. 17), Malta was conquered from the Carthaginians by a Roman army, headed by Tiberius Sempronius Longus in 218 B.C., at the start of the Second Punic War. From then on, the Romans occupied Malta uninterruptedly for some 750 years until A.D. 535, when the islands were integrated into the Byzantine Empire.

The historical sources of information about Roman Malta are scant, based on: a) archaeological finds, b) ancient documents and c) epigraphic inscriptions (six found in Gozo and two in Malta) on memorial objects in stone or bronze tablets of that period (M. Buhagiar, 2014).

A degree of information was gleaned from the writings of the Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus, who wrote in the 1st century B.C., and from Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 B.C.) the quaestor (a public financial administrator) of Sicily, based in Lilybaeum (Marsala). The latter had written about Malta when he accused Gaius Verres, the propraetor (governor) of Sicily, of having despoiled the Maltese islands of numerous precious objects for his own use. Both Diodorus Siculus and Cicero exalted the high quality of the textiles produced locally in great quantity that were traded abroad. So did the Roman poet Silius Italicus who wrote in the 1st century A.D. (M. Buttigieg, 1998).

The political status of Malta

Throughout the Roman era, Malta was regarded similarly to the 68 ‘allied towns’ (Foederata Civitas) of the province of Sicily. The islands of Malta were significantly distant from the political turmoil of the Roman capital. So much so that Cicero twice contemplated exiling himself to Malta in order to get away from the perilous political intrigues of Rome (A. Bonanno, 2005 & M. Buhagiar, 2014). It appears that throughout the Roman occupation, the Maltese islands experienced tranquility and a relatively prosperous period.

The known epigraphs provide some indication of the kind of government that Malta had during Roman times. It seems that at one time during the later days of the Roman Republic, Malta was represented in Rome by the propraetor of Sicily and a local senate. During the last days of Julius Caesar (44 B.C.) or exactly thereafter, the Sicilian city-states – and by extension, the Maltese people – were given Latin rights that included a series of privileges that could eventually lead to full citizenship (A. Bonnano, 2005). Full citizenship was granted by Emperor Caracalla to the entire Roman Empire in A.D. 212.

Social tiers in Roman Malta

There must have been three, possibly four, tiers of society on the Maltese islands, namely:

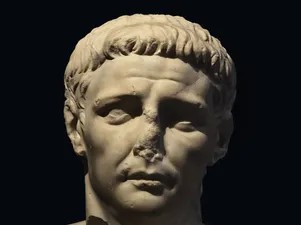

- The Elite: Wealthy landowners and administrators who were highly Romanised, based in the capital, Melite, or else in Gaulos. The opulence of the Roman Domus in Rabat reflects the wealth and power of the individuals who belonged to this class. This house was built some time in the early 1st century B.C., but was still lived in during the 1st century A.D. The busts of Emperor Claudius and his daughter Antonia found at the same site may indicate that the owner was either a close relative of Emperor Claudius (A.D. 41 – 54) or someone with close ties to the imperial administration of Malta (A. Bonanno, 2005).

- The Commercial Class: Traders, artisans, and merchants in the two capitals, Melita and Gaulos. A guild of tinsmiths/blacksmiths may have existed based on a depiction of numerous utensils on a stone slab found in one of the smaller hypogea in the St. Paul’s Catacombs necropolis. To this social class, one must add the commercial community that earned its living off imports and exports traded in the Grand Harbour with the outside world. Proof of this, in the inner creek of Marsa there were found numerous traces of warehouses – one of which contained some 250 amphorae (M. Buhagiar, 2014.) There were other buildings in the same area, possibly including a temple dedicated to the goddess Diana, protectress, among other things, of slaves (M. Buhagiar, 2014.) The subjugated may well have been the fourth tier. Slaves in Malta, although not documented, may have been profusely present to serve their masters as they did in the rest of the Roman world (A. Bonanno, 2005).

- The Agriculturalists: These may have been a mix of rich Roman agricultural entrepreneurs, judging from the widespread farm steads with their luxurious baths (thermae). These agriculturalists may have employed slaves and indigenous Maltese. The latter were possibly descendants of earlier Carthaginian occupiers. The rural natives probably maintained their distinct Punic language and cultural traditions despite Roman rule. This may be evidenced in Acts, Chapter 28, when the apostle Luke narrated about the fate of St. Paul after the shipwreck. He observed that those who came to the aid of the stranded travellers were barbaroi, meaning, they could not speak Greek or Latin, the predominant languages of the Roman and Greek worlds.

A multi-cultural society

During the Roman Republican era, when Malta was under Roman rule, that is, from 218 until 27 B.C., and also during the 1st century A.D., in the earlier years of the Roman Empire, the archipelago must have been vibrant with a mix of Greek and Punic cultural influence. These two languages were spoken, while Latin was used mainly for administrative purposes.

An example of this multi-cultural milieu is found in the two identical candelabrae (incense burners) discovered in Malta that bear two inscriptions, in both the Punic and the Greek languages. In spite of their similarity, the upper text written in the Punic script expresses a dedication to the Phoenician/Carthaginian god Melqart, while the Greek translation below refers to the same dedication, but mentions the Greek god Heracles instead. The names of the Phoenician goddess Ashtarte, the Greek goddess Hera and that of the Roman goddess Juno inscribed on pottery from Tas-Silġ archeological site, also indicate at a cosmopolitan population. Additionally, they reflect tolerance towards other religions as well as integration of non-Hellenistic divinities.

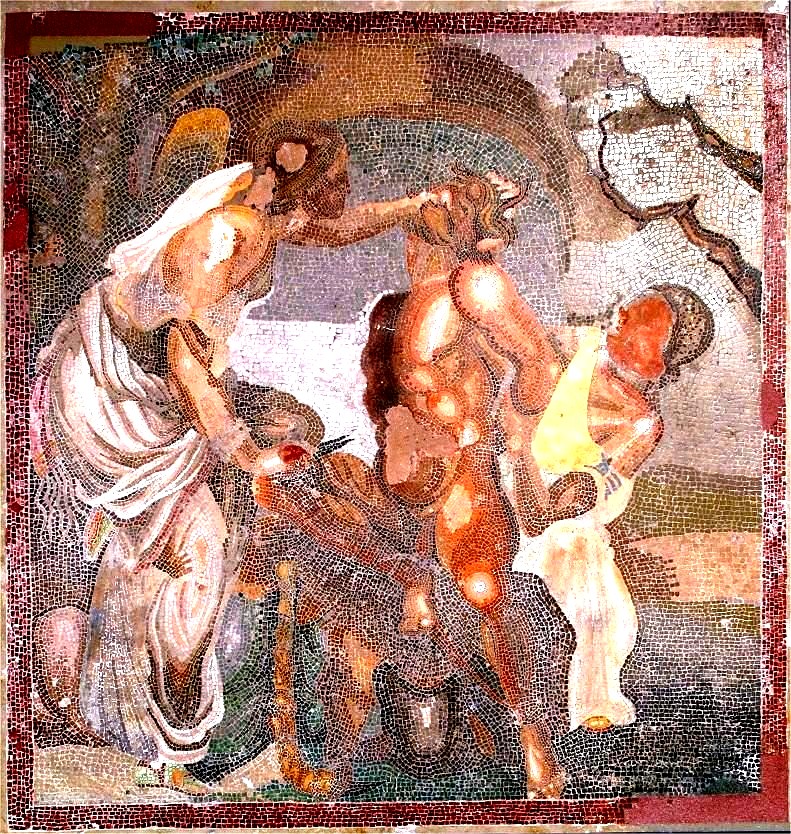

Artistically, Roman architecture as well as sculptures and mosaic works were often crafted by Greek artisans and other itinerants. In the Roman Domus of Rabat a beautiful mosaic floor adorned the courtyard, designed as it was in the opus tessaelatum style. The floor bears an overall, geometrical pattern in the trompe l’oeil style. The central mosaic depicts a bowl from which birds are drinking. The atrium of the same house was also adorned by a mosaic matrix depicting a mythological scene, possibly, two maenads (nymphs) teasing a satyr (a woodland creature). As for the performing arts, we know from the Greek insciption found on a large tombstone of an itinerant comedian and lyre player from Pergamon.

During the Roman Republican era, coins were minted in Malta as well as separately in Gozo. Their depictions of symbolic images and legends seem to have been influenced by Hellenistic and Egyptian cultures. Occasionally, these coins, which were struck in Malta, were discovered elsewhere, such as at Akragas (Agrigento), and Sciacca in Sicily and Martigny in Switzerland, suggesting a commercial link between Malta and these localities. Meanwhile, pottery discovered during excavations bears a close resemblance to both the North African as well as Campanian and Arretine ware (from Arezzo).

Roman archaeological sites

Approximately fifty Roman archaeological sites found on the Maltese islands provide insights to everyday life and cosmopolitan society (M. Buhagiar, 2014). Roman villas – interpreted as farmsteads – were constructed at various locations, and were sometimes enhanced with luxuries such as ‘Roman baths’ with their calidarium, tepidarium and frigidarium, heated by the hypocaust (an underground furnace). Such accessories were found both in Malta, at Ghajn Tuffieħa, and on the island of Gozo, at Ramla Bay.

Among the country estates is the one known as Ta’ Kaċċatura, located on the crest of the Ħas-Saptan hill, on the outskirts of Birżebbuġa. Apart from its substanial water cistern, approximately 10 x 10 x 10 metres, an olive-crusher was found at this site. Another nearby location, where evidence of the production of olive oil exists, is the archaeological site currently being excavated in Żejtun. Similarly, traces of presses, vats and mills were found at San Pawl Milqi in Burmarrad indicating that the production of olive oil must have been abundant. It is known that the obligatory tax that was owed to Rome was paid partly in cash and partly in kind, specifically in the form of olive oil (A. Bonanno, 2005).

It is also important to mention the large number of hypogea found in Malta and Gozo. The larger ones such as St Paul’s and St Agatha’s catacombs were conveniently located outside the capital’s town walls. Amongst these catacombs were found, Christian, Pagan and Jewish hypogea. These were all built some time after the 4th and 5th centuries A.D. Thus far, no Christian burial grounds have been identified prior to this period.

Malta turns Byzantine

The decision of Emperor Constantine to shift his centre of power from Rome to Byzantium (later Constantinople) in A.D. 330 sparked a gradual division of the Roman Empire into the Eastern and Western spheres of influence. The deposition of the last Roman Emperor Romulus Augustulus in A.D. 476 added more to the loss of power of Rome. During the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, in A.D. 535, Sicily and with it Malta, were incorporated into the Eastern Empire, thus marking the end of the Roman era for Malta.

Martin Morana

24 November 2025

Bibliography

Bonanno Anthony, Malta, Phoenician, Punic, and Roman. Midsea Books Ltd. 2005.

Bonanno Anthony, ‘The Maltese Artistic Heritage of the Roman Period.’ Proceedings of History Week. The Historical Society. 1984.

Bonanno Anthony, ‘The Romans in Malta,’ Treasures of Malta, Vol 1, No 1. Christmas 1994. Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti.

Buhagiar, Mario, Essays on the Archaeological and Ancient History of the Maltese Islands – Bronze Age to Byzantine. Midsea Books Ltd. 2014.

Buttigieg Michael, ‘Malta and the Classical Authors.’ Malta Yearbook, 1998.

Culcutt Alfred, ‘The Status of Malta in Roman Times’. The Malta Year Book Anthology, Vol. 1, 1993. De La Salle Publications.

Calcutt Alfred, ‘Life in Malta in Roman Times’. The Malta Year Book Anthology, Vol. I, 1993. De La Salle Publications.

Cutajar Nathaniel, ‘Recent discoveries and the archaeology of Mdina,’ Treasures of Malta, Volume VIII, no 1, Christmas 2001.

Vella, H.C.R., ‘Juno and Fertility at the Sanctuary of Tas-Silġ.’ Archeaology and the Fertility Cult in the Ancient Mediterranean. Ed. Anthony Bonanno. B.R. Gruner Publishing Co. Amsterdam. 1985.

See: Other titles, and publications by same author: please click here: