It is said that, good things in life are often within reach once we know how to look for them. However, in the early decades of the 19th century people were more concerned with scraping a living and feeding the mouths of their offspring than seeking moments of relaxation and pleasure. What with the high rate of jobless, the equally high mortality rate amongst children, that is said to have been the highest in Europe; and a plague epidemic that devasted Malta in 1813 – 14, killing some 4,600 had died?

This nowithstanding, being human requires that one seeks to revitalise his mental well-being by creating or seeking occasions by which one could distract himself from the arduous work and difficult moments that come about in a life that was short, ugly and brutish. People often sought comfort amongst their own peers and which better place to do so than at church.

FESTIVE CELEBRATIONS

For themajority of the population the arduous daily life was only interspersed with their attending the daily church services sought by the fervently Catholic Maltese. It was in the temple of God that one found solace from the life’s ‘vale of tears’. On the more mundane side however, one will quickly realise that the same religious celebrations, especially those organised in honour of particular Christian saints and other commemorations were very important. As still customary today, in the 19th century, many looked forward to such religious celebrations with great enthusiasm and anticipation as such feasts provided a silver lining that broke the dullness of daily life.

Throughout the 19th century feasts spilled more and more from the church parvis onto the town square and eventually all over the streets of the locality. The festivities became slowly but surely better organised, and as from the early 1860’s village bands started to form up to accompany and add a more cheerful aspect to the otherwise solemn processions.

Apart from these village feasts, on a national scale, the Church calendar offered two very special occasions where one could mingle with enormous huge crowds. These were the mega-pilgrimages, one being held on the feast day of St Peter and St Paul in Mdina and Rabat, known as l-Imnarja. Then there was the pilgrimage that started from Tarxien and ended in Zejtun, in honour of San Girgor. These two solemn religious celebrations where regarded as obligatory. Such important manifestations were not only spiritual obligations that needed to be fulfilled; they also instilled in the populace a sense of great anticipation. What with the processions and the long file of clergymen who accompanied, each dressed in their various vestments according to their Order and rank?

Then, following the solemn procession and the religious rituals, those who had travelled from afar needed to stay and rest there for some while to consume some refreshments. Thus they sought a shaded area, perhaps under a carob tree, or a field wall to spread out their packed lunch that they would have brought with them from home. And what a lunch it was. We have all heard of the traditional fenkata that was customary on the eve of l-Imnarja inside the wooded Buskett grove. Food and wine were accompanied with għana, the traditional long winded high pitched singing, as well as by spontaneous but traditional dancing. All this would change the previously all religious atmosphere to one of great abandon.

Here is an extract from a poem published in the periodical Giahan, of April 8, 1847. The poem illustrates the festive atmosphere following the pilgrimage of San Girgor, Interesting enough the poem states that the merry making took place in Tarxien, where the pilgrimage started earlier and not in Żejtun. Perhaps such merriment took place in both places, just as much as nowadays the festive gathering takes place in Marsaxlokk and not in Żejtun.

Min jista jpingi f’dan il fuljett Who can ever describe in this pamphlet

San Ghirgor taghna – dac iz-zufjett The feast of Saint Gregory – such merriment

Minn coll nies tara – f’dac Hal Tarxiel [sic] One meets all kinds of people – there in Tarxiel

Li trasset jieklu u imbiet bi kliel! People crowded to eat as wine flowed!

Ash-Shidyaq, a Lebanese erudite thinker and writer who lived in Malta between 1830’s and the 1840’s, when commenting about such festivities occasions states, that when people attended such festivities they got loud and vulgar to the extreme. He also mentions the various races of horses, mules and donkeys that were held as part of the festivities.

Also according to Ash-Shidyaq, the feasts held at seaside localities included a very popular game known as il-ġostra. Just as they do today, the contestants attempted to tread across an inclined pole, purposely greased with fat, and secured to a large boat, moored close to the strand. Ash-Shidyaq claims that this game was a crowd puller of the first magnitude as hundreds of people crowded nearby to watch the series of attempts at walking the pole by the young participants. The spectators often got very excited, as they cheered and jeered whenever each contestant attempted his trial in seeking to reach for the small flag stuck at the end of the pole.

Ash-Shidyaq also recalls that during his stay in Malta firework displays were already proving to be very popular especially when celebrating the feasts of saints.

In 1892, Maturin M. Ballou, an American travel writer who visited Malta in 1887 makes the following observations:

‘The amusement which seems to be most generally resorted to in Malta is that of parading through the streets in a special garb, while displaying various banners in celebration of certain church festivals. As in the ritual of the Roman Catholic Church there are some two hundred such days in the year marked for similar displays. The natives are inclined also to make these occasions an excuse for undue indulgences, and carelessness of conduct generally‘.

CARNIVAL

Religious festivities apart, the highlight of the festive calendar in the Catholic world is carnival. In 1864, Gian Anton Vassallo, author of various literary works, published a particular poem, one amongst many other light hearted verses, in a tiny publication called, Ħrejjef u Ċajt. In spite of the huge misnomer, the booklet contained neither tales nor jokes. One of the poems was called, Cliem tal-Poplu (‘The People’s Voice’) and carried a sub-title, Sibt il-Karnival (Carnival Saturday). The poem is very revealing as it tells a lot about what went on during the carnival days. As the poem is about to come to a close, Vassallo implores the authorities to let carnival remain unhindered, claiming that this was a unique occasion when the simple folk could truly let their hair down. This poem and its message to the authorities might be better understood if one assumes that it was written some years earlier in response to a particular incident which occurred in 1846.

In that year, Sir Patrick Stuart, the Governor of Malta, a strict Sabbathan, forbade the three day long carnival to commence on a Sunday as was the custom. No doubt that year, the lead revellers of carnival did not appreciate such a negative imposition one bit. Neither were they going to take this prohibition with their hands down. An ingenious plot of civil disobedience, perhaps the first in Malta, was devised. On carnival Sunday, a sizeable group of would be revellers took to the streets of Valletta, tugging along all sorts of domestic animals, such as mules, donkeys and dogs. The crowd did not wear their carnival costumes. Instead they donned their own domicile animals with all sorts of funny and colourful attire. When reaching Pjazza San Giorgio, in front of the Governor’s Palace the crowd protested vehemently and soon many became red in the face. Soon matters got out of hand as a small party split from the main crowd and headed towards the Anglican church and the residence of the Anglican pastor, situated nearby. This they did as some had got it into their minds that the new regulation had been imposed as a result of the advice given to the Governor by the Anglican Bishop. Another part of the crowd even attacked the soldiers on duty at the Main Guard in Piazza San Giorgo as these were beating the retreat. On that day, many Maltese were arrested, taken to court and jailed for their civil-turned-violent disobedience.

Turning once again to the comments of the Lebanese poet Ash-Shidyaq, we read that carnival was a major occasion for the people to make merry. During these festivities, he scorned those dressed in costumes, as men were foolish enough to dress up as women and women dressed up as men. He also informs us that the British Governor, even though not a Catholic organised a carnival ball whereby he invited not only British co-patriots but also the Maltese upper crust. Ash-Shidyaq got invited to several carnival balls and shows his annoyance at being taken for a maskerat, dressed as he was in his true traditional Arab garb! He also ruefully observes that the Maltese guests not only ate whatever was offered at the table, but quite often pinched food which they smuggled inside their sleeves to take back home for the kids!

Maturin M. Ballou, an American travel-writer mentioned earlier also describes the participation of the Maltese during carnival days:

‘The Carnival is also made much of by the common people, and indeed it would seem that all classes participate. It begins on the Sunday preceding Lent and lasts three days, during which period the populace engage, to the exclusion of nearly all other occupations, in a sort of good-natured riot, not always harmless. The most ludicrous and extravagant conduct prevails, the actors being generally masked and otherwise disguised. Hardly anything that occurs and which is designed only for diversion, and not instigated by malice, is too absurd for forgiveness. Ladies are ready to engage in a battle royal from their balconies, using confetti, dried peas, beans, and flowers, which they merrily shower upon the passers-by with all possible force. Sometimes, but this is not often, unpleasant missiles are employed and serious quarrels ensue‘.

POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCES

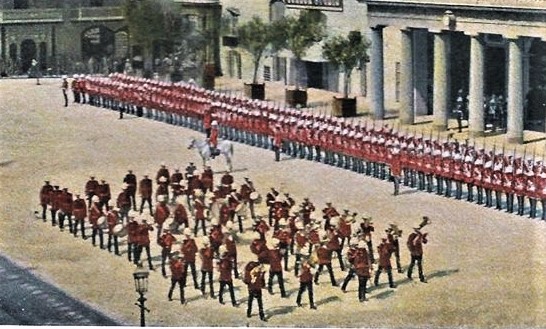

Ash Shidyaq also mentions how the Maltese enjoyed watching the military parades that were frequently held either in front of Lintorn Barracks in Floriana or else in Piazza San Giorgio, Valletta. It is a fact that throughout the 19th and early 20th century, the army and navy units or their military bands, paraded and gave displays at various localities either for a special occasion as in the case when the British won a significant battle somewhere or else simply to provide the crowds with musical entertainment as they did when invited to play in a festa. Typical venues that were often chosen for such parades were St George’s Square in Valletta, the open grounds in front of Lintorn Barracks in Floriana and Għar id-Dud in Sliema. The Maltese marvelled in admiration at the smart men in uniform, their drill and their military musical programmes.

Similarly, whenever a British royalty visited Malta the people were notified and urged to attend – and the Maltese did so more than willingly. To mention one instance, when in December 1838, the Queen Dowager, wife of William IV, came to Malta to spend a few months to recuperate her health thousands of Maltese entered Valletta to see the proceedings. Michael Galea in his short but detailed account of the queen’s arrival informs us that Valletta was decorated with a variety of street ornaments for the occasion. Governor Bouverie who welcomed the Queen at the Old Customs House landing, was of course dressed in his full military regalia as Lieutenant General. On stepping on land the Queen received a 21 gun salute fired from Fort St Angelo.Then she and her retinue were all taken in three different carriages up Crucifix Hill and to Porta Reale. The road from the Grand Harbour and Strada Reale was lined up with nothing less than six regiments. On her way her coach stopped a couple of times to receive bouquets presented to her by children as she rode past in Strada Reale. At night the Governors Palace and many other buildings both public as well as private were illuminated in various ways. This included the fjakoli on all the facades of churches and convents of the various orders in Valletta.

Another grand series of manifestations were held in 1887 when celebrating the Silver Jubilee of H.M. Queen Victoria. Similar street decorations and illuminations were held on a grand scale in Valletta. A great variety of events, some within the Palace for distinguished guests but others purposely held for the crowds to enjoy. A special train service was organised from Rabat to Valletta so that people from all that side of the island could attend. A grand tombola was organised in Piazza San Giorgo for hundreds of Maltese! Boat races were also held in the same afternoon inside the Grand Harbour.

The Governor Lord Simmons and his wife also threw a grand party at the Argotti Gardens for some 900 guests. Thousands who had gathered at the Floriana granaries to watch the distinguished guests file into the garden were not disappointed either as later that night the celebrations came to an end by a grand fireworks display that was held on the granaries.

When the when the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York visited Malta in March 1901, not only where they given the usual prominent royal welcome on arrival. When their visit came to an end, and the royal couple had embarked on their royal yacht they (and obviouosly all those present) were regaled by a carnivalesque display consisting of decorative figures that portrayed giant elephants and swans made out of papier mache and set up on barges. Firework displays also lit the skies that night.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Cassar Carmel, ‘Everyday life in nineteen and twentieth century Malta’, in The British Colonial Experience, 1800 -1964, pp. 91 -126.F.X. Cassar, Cassar Francis Xavier, El Wasita fil-Maghrifat Ahwal Malta, Ahmed Faris ash-Shidyaq.

Cassar Pullicino, A Study in Maltese Folklore, University Press.

Ballou M. Ballou, The Story of Malta, 1878. (May be traced online: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/34036/34036-h/34036-h.htm

Boissevain Jeremy, ‘Festa Partiti and the British – Exploding a Myth’, The British Colonial Experience, 1900 – 1964, pp. 215 – 229.

Borg Cardona Anna, ‘Sights and Sounds of 19th Century Valletta’, Treasures of Malta, Summer, 2001, no. 21. pp. 67 – 72.

Badger George Percy, ‘Amusements’, in Description of Malta and Gozo, pp. 126 – 136.

Ellul Michael, History In Marble, 84, 85, 203.

Galea Michael, Queen Victoria Jubilee Celebrations in Malta’, Malta – More Historical Sketches,

Michael Galea, ‘1846 – An Eventful Carnival’, Malta – More Historical Sketches,

Vassallo Gian Anton, Ħrejjef u Ċiait bil-Malti, 1863.

Ganado Albert,’Il-Versi ta’ Richard Taylor dwar l-Inċident tal-Karnival tal-1846′, L-Imnara, Vol 10, nru 4, ħarġa 39, pp. 2 – 8.