INTRODUCTION

Until a few generations ago, Malta’s Arab period was known only through a couple of dates: the Arab invasion of 870 and the Norman conquest of 1091. In between lay a long blank space filled only with supposition. According to traditional belief, the latter date was when Count Roger “set the Maltese free from the yoke of Arab/Muslim rulers”—a statement that has since been interpreted in various ways.

Indeed, it is difficult to pinpoint specific events that occurred during the Maltese “Arab period,” as very little reliable documentation has survived to set the record straight. The few documents available come from Arab or Norman chroniclers, rather than local sources. These include writings by Al-Qazwini (1203–1283) and Al-Himyari, with the latter quoting earlier texts by Al-Bakri from 1068 (J. M. Brincat, 1990).

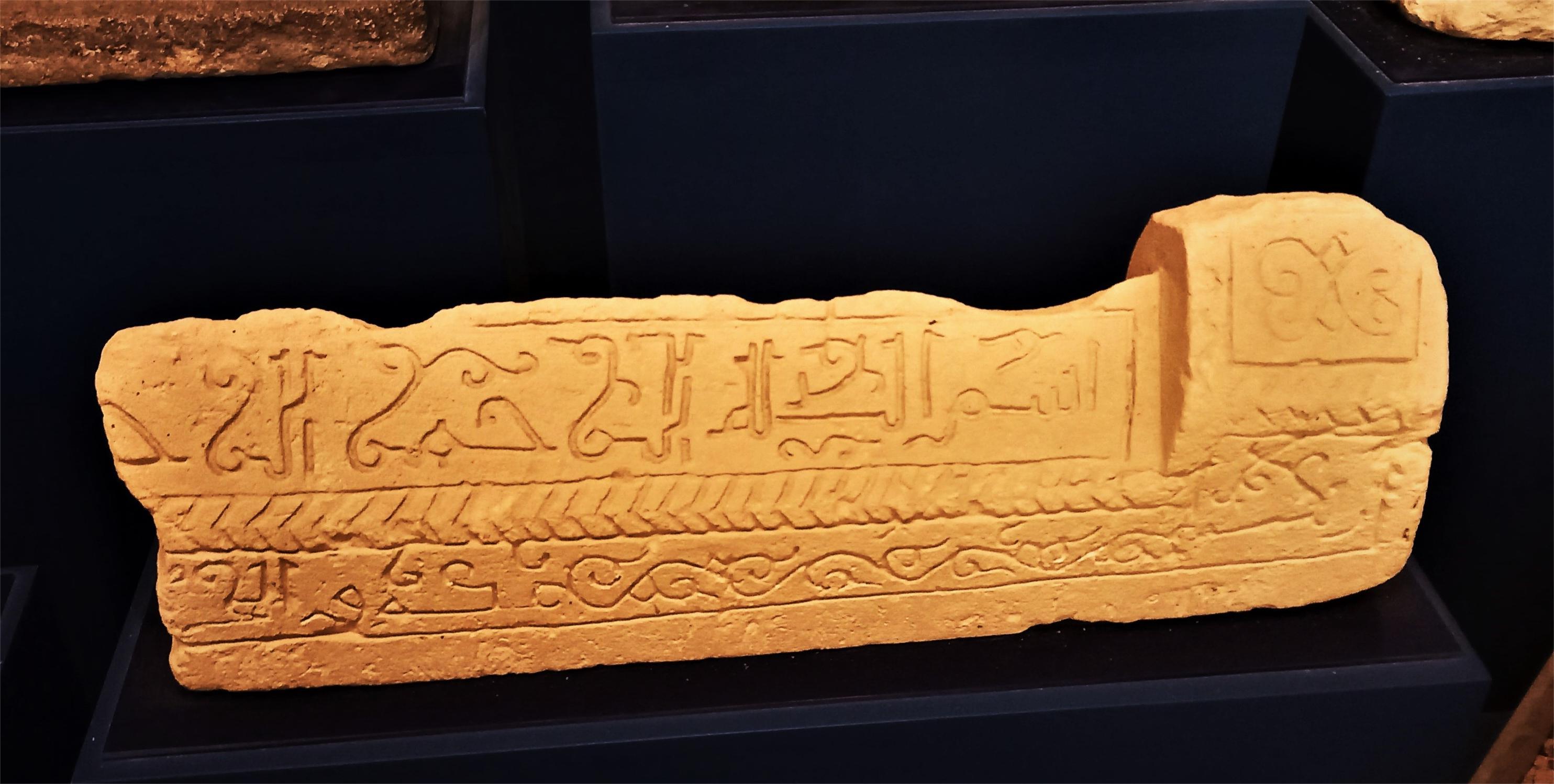

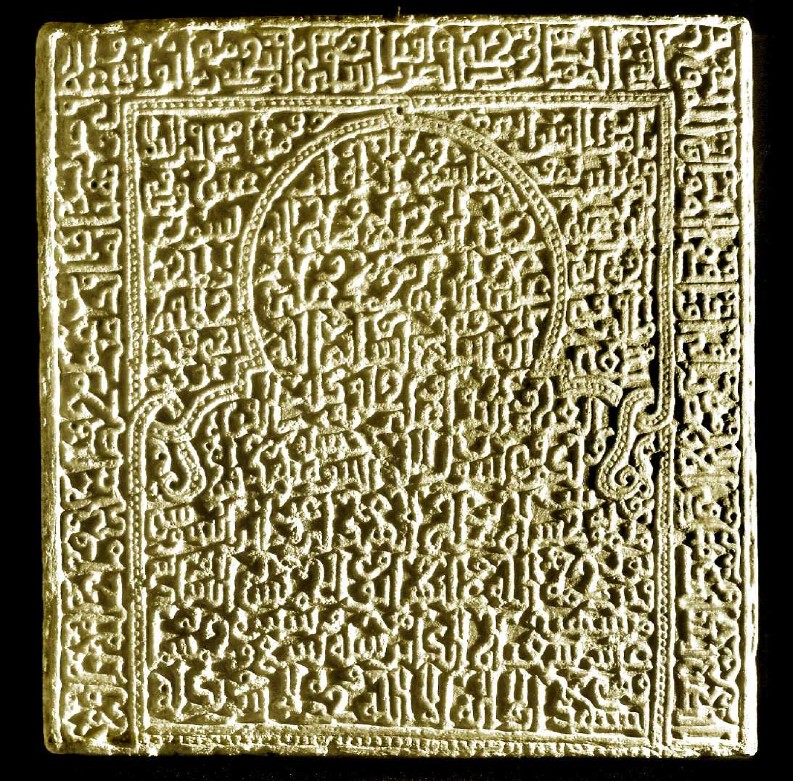

Archaeologically, apart from the Muslim cemetery discovered near the ruins of the Roman Domus in Rabat and a hoard of some 5,000 coins found near the Mdina Cathedral in 1698 (Brown & Luttrell, 1992), hardly anything survives to confirm the status of the islands or the events that took place there. The hundred or so tombs discovered in the Rabat cemetery evidence the faith and rites of the Muslim inhabitants living within Mdina (G. Wettinger, 1986). However, these may or may not reflect the beliefs and practices of the entire indigenous population. Following Muslim rites, these tombs were positioned in a south-easterly direction toward Mecca, and fourteen bear inscriptions from the Koran (Ch. Vella, 2013). Interestingly, these tombs date to the 12th century—after Count Roger’s 1091 invasion. The famous Maimuna stone, now in the Gozo Museum of Archaeology, dates to the same period (1175). This was reputedly found in Sannat, Gozo, but in truth does not reveal its real provenance (G. Bonello, 2000).

Thus, for the most part, the Arab period remains shrouded in mystery. Whether the indigenous Maltese were subjugated by the Arabs as a form of enslaved people (għabid) or regarded as protected religious minorities (Dhimmi)—like Christians and Jews elsewhere—remains a subject of intense scholarly debate. Furthermore, historians continue to discuss whether an “underground” Christian element might have survived throughout the Arab tenure (G. Wettinger, 1986).

The Westward Expansion of Islam

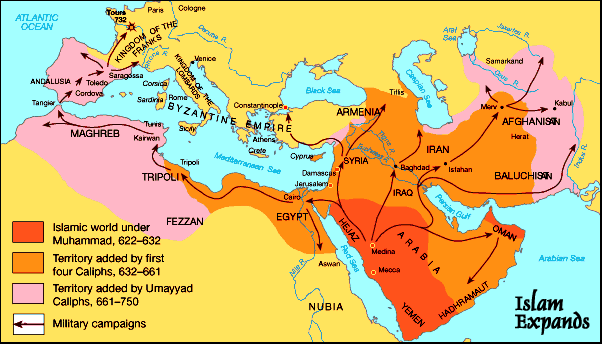

To unravel this “dark” period of Malta’s history, one must consider the broader context of Arab domination as it unfolded across the Mediterranean. From the 7th to the 15th century A.D., Arab military forces and Muslim zealots crossed from North African shores at frequent intervals.

Initially, this westward shift originated in the Middle East—particularly Egypt—driven by political tensions and economic instability. This period also saw constant migrations of nomadic tribes from Arabia toward the Maghreb. These military movements, often motivated by the search for living space and resources, were accompanied by large waves of migratory peoples.

Along the way, the antagonistic Berber tribes of the Maghreb were initially fought, but eventually assimilated by the invaders, who utilized them to conquer new territories. Ultimately, these eastern groups settled in Kairouan and Carthage in Ifriqiya (roughly modern-day Tunisia), and later in the newly founded city of Fez in Morocco.

The next step for these forces was to cross the Strait of Gibraltar into the Iberian Peninsula. Within a few years, the region was practically overrun by Arabs and Berbers, who overwhelmed the Visigothic Christians. Over time, many native Christians integrated into the new society, adopting the Arabic language while maintaining their faith; these individuals became known as Mozarabs (musta‘rab).

In both the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa, Christian communities often survived by paying a specific tax (Jizya) to their Muslim rulers. Contrary to common belief, the early Arab conquests were often driven less by religious zeal and more by the quest for territorial gain and wealth. Islamization typically followed conquest, leading to integration into a dominant culture—a process that was, more often than not, entered into willingly.

The Arab Invasion of Sicily

In the late 8th century, prior to 827 AD, North African Arab forces launched numerous incursions against Byzantine Sicily. Eventually, Ziyadat Allah I the Aghlabid Emir of Ifriqiya, dispatched a military force from Kairouan. This expedition sought what Leonard Chiarelli (2011) describes as a “lucrative adventure: the conquest of Sicily.”

The Arabs initially advanced toward Syracuse, the capital of Sicily at the time, then under the Byzantines, but the city withstood various onslaughts for some seventy years. Consequently, the Aghlabids proceeded to conquer other regions of the island. In 831, they successfully settled in Palermo, then the second most important city in Sicily. It was not until 902 that the entire island was fully brought under Aghlabid control.

The Arab Conquest of Malta

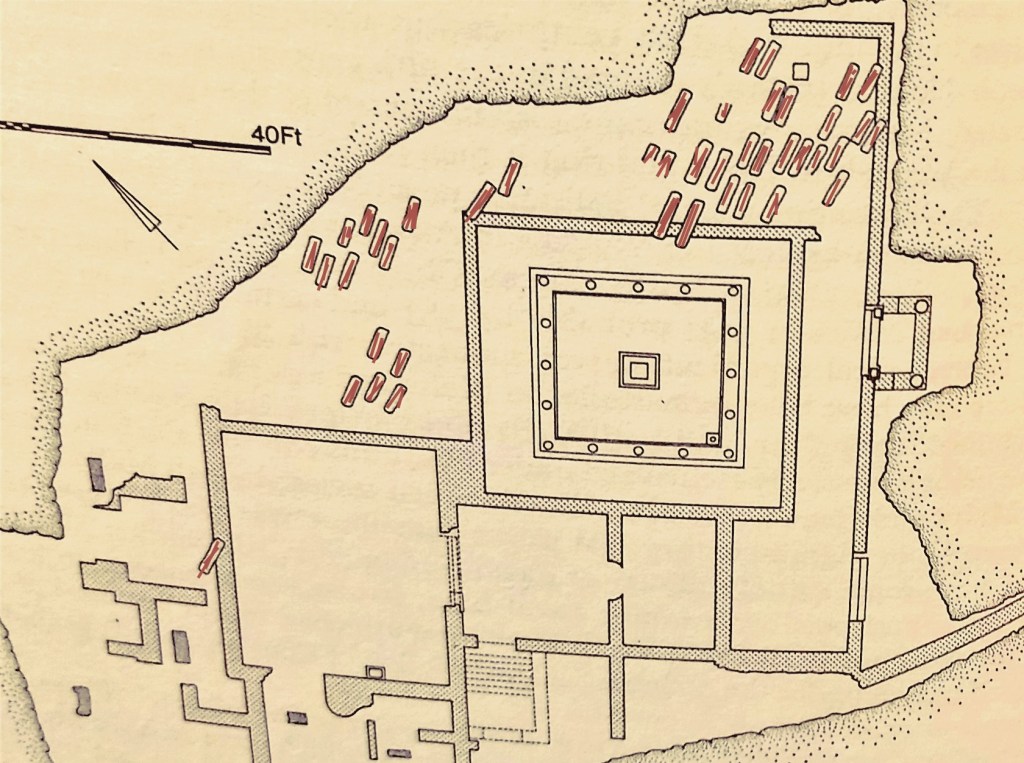

In 869/70 AD, an Arab force sailed southward across the Sicilian Channel to seize the Maltese archipelago. At the time, Malta was under Byzantine rule, administered most probably from Syracuse. Whether the local population offered stiff resistance remains a subject of debate, though archaeological evidence offers some clues. Excavations at the Tas-Silġ sanctuary and the ruins of San Pawl Milqi reveal levels of destruction datable to this period, suggesting a violent transition.

Interestingly, Syracuse fell to the Arabs in 878, only after the capture of Malta. It is perhaps no coincidence that in that same year, a “Bishop of Malta” was reportedly imprisoned in Palermo.

Following the conquest, traceable evidence of Christianity disappears from the Maltese archipelago for several centuries. No other Maltese bishop is mentioned in historical records until 1156, well into the Norman period.

Furthermore, ancient chroniclers such as al-Bakri cited by al-Himyari claimed that Malta remained largely uninhabited during the 10th century. This controversial assertion has yet to be fully reconciled with archaeological findings. Excavations in Mdina during the 1990s yielded pottery fragments dating to the 10th and 11th centuries (N. Cutajar, 2001), which partially counters the “uninhabited” theory. Logically, it is unlikely the Arabs would have abandoned the islands after such a strategic conquest, as doing so would have allowed Byzantine forces to reoccupy them immediately.

In 1038, the Byzantine General George Maniakes attempted to reconquer Sicily. Roughly a decade later, in 1048/49, a Byzantine force attacked Malta. According to historical accounts, the Arab leaders invited the local “slaves” (għabid) to take up arms alongside them to repel the invaders. The locals complied, successfully fending off the Byzantines. This event implies that the Arabs had maintained firm control over a subjugated indigenous population for some time.

If the Maltese population converted to Islam during this period, no definitive archaeological traces—such as mosques—remain in Mdina or in the countryside to prove it. A similar phenomenon is observed in Sicily, where virtually no original Islamic religious architecture survives from the period of Arab rule. Notable “Arab” architectural elements, such as those found in the Martorana Church or the Zisa Palace (Al-Aziza) in Palermo, actually date to the subsequent Norman period, representing a “Fatimid-Norman” hybrid style rather than purely Arab construction.

Count Roger’s Expedition to Malta

In 1061, Count Roger I and his Norman army crossed the Strait of Messina to begin the conquest of northern Sicily. By 1071, he had successfully defeated the Arab forces in Palermo. Twenty years later, in 1091, Count Roger headed south to take the town of Noto, the final Muslim stronghold in Sicily. From there, he marched to the coast to embark his fleet and set sail for Malta.

Upon landing on Maltese shores, Count Roger encountered little resistance. The gates of the capital, Mdina, were opened to him by the island’s Ħakim. Roger demanded total allegiance and recognition as the islands’ new overlord. Crucially, he insisted that the Arab leaders immediately release all captive Christians held within the city.

According to Goffredo Malaterra, Count Roger’s chronicler, these captives were likely of Greek or Byzantine origin rather than indigenous Maltese, as they greeted their Norman liberators by chanting the Kyrie Eleison (Greek for “Lord have mercy”). After securing his terms in Malta, Count Roger sailed to Gozo, where his army plundered the island before returning to Sicily.

Evidence of the anxiety caused by this invasion may exist in the archaeological record. In 1698, a significant gold hoard was discovered in Mdina. Consisting mainly of Arabic coins, the hoard’s most recent coin dates to just after 1087, closely coinciding with the Norman assault three years later.

This discovery suggests that a wealthy resident—or perhaps a local institution such as the town council or the cathedral chapter—may have buried the treasure, fearing the pillaging that often accompanied a foreign invasion (H. W. Brown & A. Luttrell, 1992).

The Arabs – Post-Count Roger

Following the Norman intervention of 1091, local administration and the daily life of the Maltese inhabitants remained largely unchanged. The Arab leaders were, however, obliged to pay an annual tribute to the Norman court in Palermo.

Regarding the economic landscape of the time, it is noteworthy that a rare Maltese gold coin—a Fatimid quarter-dinar (or rub’i)—is held by the authoritative numismatist André P. de Clermont. The inscription on the coin’s reverse indicates it was minted in Malta in 1079 AD, just over a decade before the Norman arrival. This suggests that late 11th-century Malta engaged in high-value trade significant enough to warrant its own mint (J.C. Sammut & E. Azzopardi, 2009).

The events of 1091 did not mark the end of the Muslim period in Malta. Indeed, as in contemporary Sicily, “Latin” culture was largely confined to Norman strongholds and had not yet permeated the wider population (Ch. Dalli, 2006). It was not until 1127, under Roger II, that the Normans established a permanent garrison and a formal administration in Mdina. Even under Christian rule, a large segment of the population remained Muslim. This is evidenced by Bishop Burchard of Strasbourg, who having visited Sicily and Malta reported in 1175 that the population of Malta was still predominantly “Saracenic”—a term used at the time to describe Arabic-speaking Muslims.

It is noteworthy that in Sicily, Arabic script and language persisted well into the Norman and subsequent Swabian (Hohenstaufen) periods. As late as 1153, a Christian psalter was produced in Sicily, in three languages: Greek, Latin, and Arabic (H. Bresc & G. Wettinger, 1986). This indicates that even Christians of the Byzantine rite in Sicily continued to speak and write in Arabic during this era.

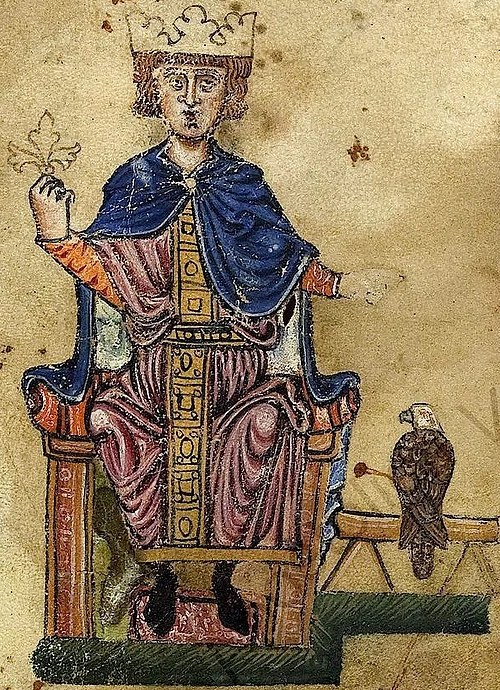

According to the renowned Arab historian Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), the Swabian Emperor Frederick II—who ruled Sicily and Malta—exiled the “last of the Arabs” from these territories twice. The first wave followed a Sicilian uprising in the 1220s, and the second occurred during his final decade as emperor in the 1240s. This suggests that Malta remained predominantly Muslim throughout the Norman period and into the Hohenstaufen era.

Indeed, a 1240 report by Frederick II’s royal commissioner, Giliberto Abate, records that the Maltese islands were inhabited by 836 Muslim families, compared to only 250 Christian and 33 Jewish families. There is ongoing historical debate regarding why the number of Christian families remained so low, especially since Frederick II had reportedly ordered the exile of non-converting Muslims to Lucera between 1221 and 1225 (Ch. Vella, 2013). This raises the enduring question: who exactly were the “Muslims” expelled from Malta during the final clearing in 1249?

The Maltese language today remains a living testament to this medieval period. Specific Islamic and liturgical terms survived the transition to Christianity. Words such as Alla (God), Għasar (afternoon prayer/vespers), and Randan (Lent/Ramadan) provide linguistic proof of the deep-rooted Arabic-Muslim culture that withstood the eventual conversion to Christianity in the Late Middle Ages.

© Martin Morana

January 27, 2026

Bibliography

Amari Michele, Storia dei Musulmani di Sicilia. Felice de Monnier, Firenze. 1854.

Barnard John, ‘Malta under Muslim rule’. The Malta Independent, 1 August 1993.

Bonello Giovanni, ‘New Light on Maimuna’s tombstone’, Histories of Malta – Deceptions and Perceptions Volume one. Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti. 2000.

Bresc Henri, ‘Arab Christians in the West of the Mediterranean (XI – XIII centuries), Library of the Mediterranean History, Ed. Victor Mallia-Milanes. Mireva Publications. 1994.

Brincat Joseph M., Il-Malti – Elf Sena ta’ Storja. PIN Pubblikazzjoni Indipendenza. 2006.

Brincat Joseph M., ‘Whatever happened in 870?’ The Sunday Times, August 5, 1990.

Brincat Joseph M., ‘Muslim Malta and Christianity in Gozo?’ The Times, December 6, 2010.

Brincat Mark, ‘Christianity in Malta under the Arabs’. The Sunday Times, February 11, 1990.

Brown Helen W., ‘The Coins of Muslim Malta.’ Melita Historica, Vol IX, no 1. 1992

Chiarellli Leonard C., A History of Muslim Sicily. Midsea Books. 2011.

Cutajar Nathaniel, ‘Arabes et Normande a Malte’, Dossiere d’Archaeologie -Malte. N. 267, Octobre, 2001.

Dalli Charles, Malta – The Medieval Millenium. Midsea BooksLtd. 2006.

Lehmann Johannes, Die Staufer – Glanz und Elend eines deutschen Kaiser-geschlechts. Bertelsmann Verlag, München. 1985.

Luttrell Anthony T., Approaches to Medieval Malta, The British School at Rome, London. 1975.

Luttrell Anthony T., ‘The Hoard of Muslim Coins’: 1698. Melita Historica, Vol IX, no 1. 1992.

Mercieca Simon & Cassar Xavier, ‘Christians in Arab Malta’ (4), The Malta Independent, 14, March 2016.

Sammut J.C. & Azzopardi E., ‘A unique medieval Fatimid gold coin of Malta’, Treasures of Malta, Vol. XVI, No. 1, Christmas 2009, No 46.

Vella Charlene, The Mediterranean Artistic Context of Late Medieval Malta. Midsea Books. 2013.

Wettinger Godfrey, ‘The Arabs in Malta’, Malta – Studies of its Heritage and History. Mid-Med Bank Limited. 1986.

Wettinger Godfrey, ‘Did Christianity survive in Muslim Malta? – further thoughts’, The Sunday Times, November 19, 1989.

Other publications by same author … please click here: https://kliemustorja.com/informazzjoni-dwar-pubblikazzjonijiet-ohra-tal-istess-awtur/