ENTERTAINMENT in BRITISH MALTA (1800 – 1900)

Sorrow and laughter

In the early 19th century when the British military took over the islands of Malta and Gozo, the Maltese population had very little to entertain themselves with. On the personal level those lucky enough who could earn a living did so to survive. Very few Maltese could work to entertain themselves with the money earned. Entertainment often came their way in simple doses, either as personally created amusements or else whenever there were religious or national celebrations.

Festive celebrations

Albeit their religious and spiritual intentions, feasts were probably the most popular form of entertainment. I will start by mentioning the likes of pilgrimage feasts such as the Imnarja as well as the San Girgor pilgrimage. The Maltese attended such celebrations in their thousands, some as participants others as onlookers. The Maltese saw the prospect of enjoying the spectacle throughout, the solemnity of the procession with so many clergymen dressed in their particular cloaks.

Following the procession and having paid respect to the titular saint for which the devotional procession and prayers were held, the populace having come from their home towns carrying food and drink would settle down in a shady area, such as a carob tree or beneath a field wall in the vicinity of the sanctuary to enjoy their lunch. And what a lunch it was. The food and drink feted would be accompanied with flasks of wine. Merriment in the way of għana and possibly dancing could change the solemn atmosphere into one of merriment.

This is what happened on the eve of Mnarja at Buskett and Rabat as well as at Zejtun’s old parish church dedicated to St Catherine but better known as San Girgor.

Ash-Shidyaq, a Lebanese poet, philosopher, scholar and writer who lived in Malta for some fifteen years, between 1830’s and the 1940’s reveals that during the feast days the Maltese people The same author however, scornfully observes that during feasts the people got loud and vulgar to the extreme. He also mentions the various races of horses, mules and donkeys that were held as part of the festive entertainment of the masses. According to Ash-Shidyaq, the saint’s feasts at the sea-side localities included a very popular game known as il-ġostra. In the game, contestants attempt to walk on a pole that was secured to a floating barge. Ash-Shidyaq says that this game was a crowd puller of the first kind as thousands of people flocked to watch the spectacle. The crowd often got excited, cheered and jeered according to the balancing skills of the contestant.

Ash-Shidyaq also recalls that during his stay in Malta firework displays were already proving to be very popular especially when celebrating feasts of saints. In 1892 Maturin M. Ballou, an American travel writer who visited Malta in 1893 as part of his journeys on this side of the European continent observed the following behaviour of during a feast.

‘The amusement which seems to be most generally resorted to in Malta is that of parading through the streets in a special garb, while displaying various banners in celebration of certain church festivals. As in the ritual of the Roman Catholic Church there are some two hundred such days in the year marked for similar displays, the festivities of this sort appear to be chronic, and absolutely pall upon one. The natives are inclined also to make these occasions an excuse for undue indulgences, and carelessness of conduct generally‘.

Ash Shidyaq also mentions how the Maltese would flock to the Floriana parade ground and Pjazza San Giorgio in Valletta, to enjoy the military parades which the British military put on from time to time.

Entertainment on a personal level

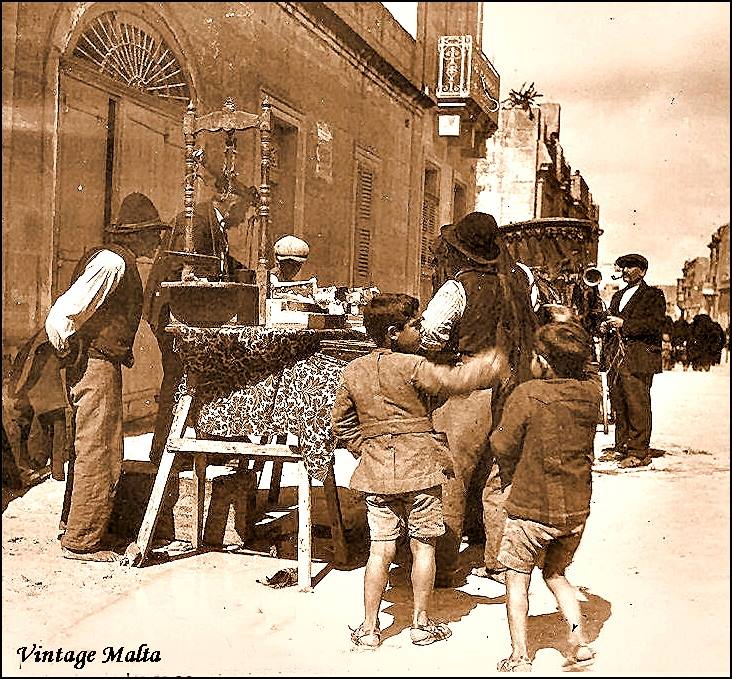

In the towns and villages there were many musicians in towns and villages who played a variety of instruments such as as string, brass, cymbals, base drum, drums and some wood. Ash-Shidyaq noted that these musicians were often hired to entertain private functions. For instance, musicians were sometimes hired by the husband whose wife was about to give birth to their child. Expectant mothers would thus be entertained on the last days of their pregnacy by a musician or two who would play outside the house. Musicians would also return to play to the same family and entertain the parents some time after the birth of their child. Bands would also be hired to send off emigrants who were to leave home for good to settle in another country; at the time immigration was widespread, with most people settling along the whole of the Mediterranean littoral. Those individuals who returned home were similarly treated with the playing of musical instruments as a way of welcoming them back.

The theatre scene

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, the British took over the management of the Teatro Pubblico, which they later named the Teatro Manoel. By 1810, the theatre had been renovated and was staging performances of all types to audiences mostly made up of British officers, soldiers and sailors, as well as a small circle of Maltese spectators. The theatre offered a wide-ranging stage entertainment. The Lebanese writer Ash-Shidyaq for instance mentions that during his time in Malta, he once attended a show there in which an Italian illusionist performed magic tricks.

It seems that performances at the Manoel Theatre were often interrupted by improper comments and noises whenever British soldiers and sailors attended. J. Cassar Pullicino, (1980) mentions that William John Stevens, an English notary working in Malta, was so disgusted with the unruly behaviour of his compatriots that he appealed for and was provided with funds to open another theatre for a more discerning and better behaved English speaking audience. He was provided with 2,000 English pounds and a new theatre was opened in the old Jesuit College. This ‘English Theatre’ operated up until 1832, and then closed its doors for good.

Another small theatre that was patronised by the British in his book Maltese Travesties and Dynasties Giovanni Bonello points out that in 1803, there existed It-Teatrin ta’ Marsamxett which was patronised by foreign miltiary personnel. Bonello cites an account of a brawl that broke out once, amongst foreign patrons during a ball.

The demand for entertainment and the yearning for higher quality performances, especially when it came to opera, proved to the British that the Teatro Pubblico was too small for putting up large scale productions. Thus, in 1862, it was decided that a new theatre was to be built. The theatre was designed by Edward Middleton, who was also the architect of Covent Garden in London. The Royal Malta Opera House opened its doors in 1866.

Apart from the performance itself, the intervals throughout the show proved to be a great determining factor for the theatre buffs to enjoy. This was the moment when one could see and be seen as all attending would flaunt their own personal fashionable attire while the British officers would be only too happy to attend in their military uniforms.

Throughout the decades that followed the impresarios of the theatre contracted mostly Italian productions. It was at the Royal Opera Theatre that the bigger productions such as the spectacular Italian operas were held. The British in Malta also fell in love with the Italian musical genre.

The Teatrin – The Maltese way

As the 19th century progressed, the love for the theatre by the Maltese dilettanti also grew, so that by the mid-19th century, a sizeable following of theatrical performances was noticeable both amongst producers as well as audiences. By the 1840’s there emerged several playwrights who could supply their own modest productions intended mostly for an unpretentious Maltese audience to enjoy. These shows were held in small theatres in various parts of the island and became known as the teatrin. Perhaps the very first established playwright was Luigi (Wiġi) Rosato, who from 1836 onwards started to pen and produce mostly drama. His first play, Catarina, was the first ever to be written in Maltese. By 1864, Rosato had his own drama company, L’Aurora.

Carmelo Camilleri (1821 – 1903), was another prolific playwright and one of the best stage comedians. Amongst his popular comedies there were: Kull Par Għal Paru, 1844, (‘Each to his own kind’), It-Tapit, 1853, (‘The Carpet’) and so many others in later years. In 1892 his company was taken over by the Mikelanġ Borg who remains up to these days for his Żeża tal-Flagship which he produced in the early 20th century. In 1896 Borg was able to present his first performance at the Royal Opera House.

Then there was also Pietro Paolo Castagna, (1827-1907), the famous Maltese historian who wrote three popular plays: L aħħar tas Sena (‘End of Year’), a farce that was staged in 1856; Il Cungres tas Sefturi, (‘The Servant’s Congress’) and others. During the late 1850’s, Castagna founded a dramatic company named Il Cumpagnia Filodramatica Vittoriosa.

Many of these small theatrical companies often performed in extremely humble venues. Small theatre halls were provided for by proprietors owning warehouses. One theatrical group held shows in the ditch outside Valletta, somewhere below Porta Reale, (City Gate). In Żejtun there was a small drama group performing in the house of a certain Giovanni Diacono. Another teatrin was opened in Msida and was called La Pace; yet another was opened in Qormi, called il Progress while In Vittoriosa (Birgu) there was the Teatro Vittoriosa. Many companies performed to audiences sometimes in broad daylight as the theatrical performance was held outdoors for all the neighbours to watch for free. At this time, the populace could not afford to pay admission fees, and besides, in many theatres there was no proper illumination for stage and auditorium. Moreover, morality also dictated that no self-respecting family would venture out of home after sunset. There might also be the fear in the Maltese psyche that roaming around in pitch dark streets would be tantamount to inviting trouble from a lurking ill-intentioned rogue.

The Opera Blockbusters

The 19th century was the time when opera ruled supreme, thanks to the great works of the Italian composers such as Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini. By the mid-19th century this musical genre had reached its golden age. What with the romantic and dramatic script, the lyrics, the musical compositions and very importantly, the stage decor? These stage performances soon became much sought after by the public, much in the same way as the blockbuster movies do today. Indeed they became known as the ‘grand operas’. The whole production was enhanced by exotic period costumes that pleased the eye. Watching a grand opera was considered to be a highly charged emotional experience.

The most popular operas ever staged in Malta in the 19th century were:

i) La Traviata, first performed in Malta in 1835; up to present this opera has been performed 596 times;

ii). Il Barbiere di Siviglia, first performed in 1820, and since then has been performed 421 times.

iii.) The Rigoletto – first performed in 1853 and has since been performed 410 times.

Carnival

Surely the highlight for the populace to enjoy itself was during the carnival days, just before the more sombre days of Lent. In 1864, Gian Anton Vassallo, another playwright and author of various literary works published a poem in his small booklet of verses, titled, Ċajt u Stejjer, that says a lot about how the Maltese enjoyed carnival. In the poem he implores that these days should be well observed by one and all as essential to the expectations of the Maltese populace. The poem is called Cliem tal-Poplu (‘The People’s Voice’). In his humorous verses Vassallo points out that carnival was a unique occasion in the year’s calendar when the poor and the miserable made merry. He might have written this poem some time earlier in response to an incident which occurred in 1848 Sir Patrick Stuart the Governor of Malta and a Sabbathan, when in office at the time forbade the carnival merriment to kick off on Saturday.

The Lebanese poet Ash-Shidyaq states that carnival was a major occasion for the people to make merry. During these festivities, he says, men were foolish enough to dress up as women and women dressed up as men. This was the time to wear costumes and masks and get stone drunk. Even the British governors of Malta, who were no Catholics, joined in on the local traditions. Ash-Shidyaq got invited to several carnival balls that were organised at the Governor’s Palace. Ash-Shidyaq got annoyed, when, dressed in his traditional Arab garb, he was often mistaken for a maskerat! He also ruefully observes that the Maltese guests not only ate whatever was offered at table, but quite often hid food snacks inside their sleeves to smuggle out to consume at home.

An incident which occurred in 1846 helps prove the point that it was wise not to mess around with the Maltese in their carnival revelry. In that year the Governor of Malta, Sir Patrick Stuart, a strict Sabbatharian, felt that the Maltese should leave Sunday, a holy day, out of the four day celebrations. No doubt, the Maltese carnival enthusiasts, keen as they were to get their en plein through all of the carnival days, did not accept such an intrusion meekly, especially when the order came from the British Governor a Protestant. An ingenious plot of civil disobedience was devised. On carnival Sunday, an angry mob took to the streets of Valletta, tugging along their domestic animals, such as goats, donkeys and dogs. On the day, the angry mob did not wear any costumes however their pets did, as they were adorned with a variety of crazy paraphernalia to make mockery of the decree. The crowd protested vehemently in Pjazza San Giorgio, in front of the Governor’s Palace. Then, a small part of the crowd splintered and headed towards the residence and church of the Anglican pastor, situated a few blocks away down Strada Teatro. This they did because it was rumoured, and so the mob was convinced, that it was the English Anglican Bishop who had advised the Governor to impose such restrictions on the day of the Lord. Another part of the crowd worked itself up into a rage and attacked n army contingent that was beating the retreat in the square. Many were arrested, put on trial and jailed for disturbances and threats.

Maturin M. Ballou, an American travel-writer who was in Malta in 1893 describes in his book on the history and travelogue of Malta how the Maltese participated in carnival:

‘The Carnival is also made much of by the common people, and indeed it would seem that all classes participate. It begins on the Sunday preceding Lent and lasts three days, during which period the populace engage, to the exclusion of nearly all other occupations, in a sort of good-natured riot, not always harmless. The most ludicrous and extravagant conduct prevails, the actors being generally masked and otherwise disguised. Hardly anything that occurs and which is designed only for diversion, and not instigated by malice, is too absurd for forgiveness. Ladies are ready to engage in a battle royal from their balconies, using confetti, dried peas, beans, and flowers, which they merrily shower upon the passers-by with all possible force. Sometimes, but this is not often, unpleasant missiles are employed and serious quarrels ensue‘.

‘The day after the close of the carnival, those who have taken any extravagant part in the revels, or who have been over self-indulgent, repair to the small church of Casal Zabbar, called Della Grazia, where they humble themselves by way of penance for their follies and excesses‘.

‘To-day, in Rome as in Malta, the Carnival is losing its popular interest.‘

As to this final remark by Ballou, if true, is interesting.

Folk Dances

Many are those who modern folk dancing suggest that these have originated in the 18th or 19th century. Without evience such as representations in painting, drawing, statuary or any music that specifically shows the origins of dancing are a conjecture and contemporary folk dance does not qualify for authenticity. We do know however, that there were times that dancing did take place, first and foremost as already mentioned during carnival. But were there other occasions when it was appropriate to dance? Maturin Ballou provides us with his own first hand witness account of Maltese dancing. Unfortunately he does not reveal where he saw it, except that he spied dancers performing in an inland village, and we do not know what the occasion was. He observes that the dance he watched was of no particular grace. These were dancing to the accompaniment of two instruments, namely a tambourine and a horrible makeshift bagpipe made out of an inflated dog’s skin. He is obviously referring to iż-żaqq.

‘In the little inland villages of stone cabins a pastoral air prevails; but one occasionally witnesses novel scenes and unique performances, such as small groups of peasantry dancing after a style erratic enough to suit a Comanche Indian. The accompanying music, on the occasion we refer to, was produced by a home-made instrument, which reminded one of a Scotch bagpipe, only it was, if possible, still more trying to the ears and nerves. It is known here as a zagg. It is made of an inflated dog-skin, and is held under the musician’s arm, with the defunct animal’s legs pointing upward. A sort of pipe is attached to this air-bag, which is played upon with both hands. It is hardly necessary to say that a more ungainly instrument could not well be conceived. A tambourine accompaniment, performed by another party, is usually added to the crude notes of the dog-skin affair. To the music of these simple instruments the bodies of the dancers sway hither and thither in a singular and apparently purposeless manner. There was, however, a certain uniformity in the movements of the participants which showed design of some sort. The dancers seemed to lose themselves in the process, and to enjoy the queer pantomime, after a fashion. For significance of purpose, or poetic design, this exhibition will not compare with the tarantella, which the peasantry dance in southern Italy, or with the dashing firefly dance of the common women of St. Thomas, in the West Indies. (The Story of Malta, p. 248, Ballou, 1893).

Bibliography

A British Theatre in Valletta (1812-1832), J. Cassar Pullicino, The Sunday Times, 30th August, 1980.

‘Everyday life in nineteen and twentieth century Malta’, Carmel Cassar, in The British Colonial Experience, 1800 -1964, pp. 91 -126.

‘Features of an island economy’, Arthur G. Clarke, The British Colonial Experience, 1800-1964, pp. 127-154.

Feasts: El Wasita fil-Maghrifat Ahwal Malta, Ahmed Faris ash-Shidyaq; translated into Maltese by F.X. Cassar. pp. 34 – 66.

Feasts: (ġiostra): https://www.facebook.com/MaltaRightNow/videos/10154653316514026/

The Story of Malta, Maturin M. Ballou, 1878. (May be traced online: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/34036/34036-h/34036-h.htm

El Wasita fil-Maghrifat Ahwal Malta, translated into Maltese by F.X. Cassar pp. 39 – 42.

‘Festa Partiti and the British – Exploding a Myth’, Jeremy Boissevain, The British Colonial Experience, 1900 – 1964, pp. 215 – 229.

‘Sights and Sounds of 19th Century Valletta’, Anna Borg Cardona, Treasures of Malta, Summer, 2001, no. 21. pp. 67 – 72.

‘Amusements’, in Description of Malta and Gozo, George Percy Badger, pp. 126 – 136.

History In Marble, Michael Ellul pp. 84, 85, 203.

1887: Queen Victoria Jubilee Celebrations in Malta’, Michael Galea, Malta- More Historical Sketches, pp. 6 – 14.

‘Political Satire in Malta’: 1860’s – 1932, William Zammit, Treasures of Malta, Summer, 2004, no 30, pp. 74 – 78.

Lost Maltese Newspapers of the 19th Century, Arnold Cassola.

‘History of the theatre in Malta – The 18th century’, Joseph Eynaud, pp. 601 – 605, Heritage vol. 2.

Oh Żmien Ħelu, Il-Palk ir-Radju u Jien, Josephine Mahoney, pp. xxii – xxv.

Opri Popolari fil-Gżejjer Maltin, Tony C. Cutajar, p. 14.

‘Outlines of Theatre History in Malta’, Mario Azzopardi, Malta an Intimate Survey, pp. 33-44.

‘1866 – The Inauguration of the Malta Opera House’, Michael Galea, More Historical Sketches, pp. 73 – 78.

‘Nineteenth Century Maltese Theatre – Luigi Rosato and Carmelo Camilleri’, Joseph Cassar Pullicino, The Manoel – Journal of the Manoel Theatre, Vol. , No1, 1996-1997, pp. 41 – 45.

‘1846 – An Eventful Carnival’, Michael Galea, Malta – More Historical Sketches, pp. 80 -86.

El Wasita fil-Maghrifat Ahwal Malta, translated into Maltese by F.X. Cassar pp. 41, 42.

Ħrejjef u Ċiait bil-Malti, Gian Anton Vassallo, 1863.

‘Il-Versi ta’ Richard Taylor dwar l-Inċident tal-Karnival tal-1846′, Albert Ganado, L-Imnara, Vol 10, nru 4, ħarġa 39, pp. 2 – 8.

‘1846 -An Eventful Carnival’, Michael Galea, Malta – More Historical Sketches, 1971, pp. 86 – 90.

The Story of Malta, Maturin M. Ballou, 1878. (May be read online:

For other publications by the same author … please click here: https://kliemustorja.com/informazzjoni-dwar-pubblikazzjonijiet-ohra-tal-istess-awtur/