The Exiles of the Risorgimento in Malta

Introduction

Following Napoleon’s exile to Elba, representatives of many European states met in what became known as the Congress of Vienna (1814-15). The discussions were aimed at ensuring a stable and peaceful Europe, following the turmoil and destabilisation of many monarchies during the Napoleonic Wars. Ultimately, the representatives sought to create a balance of power and peaceful co-existence between the states. With new territorial boundaries established, the old regimes resumed their despotic rule over their subjects. However, by this time many peoples were aspiring for a more liberal government, while others wanted to be free from their foreign masters. Thus, in the years that followed, it was inevitable that uprisings against the absolute rulers would take place.

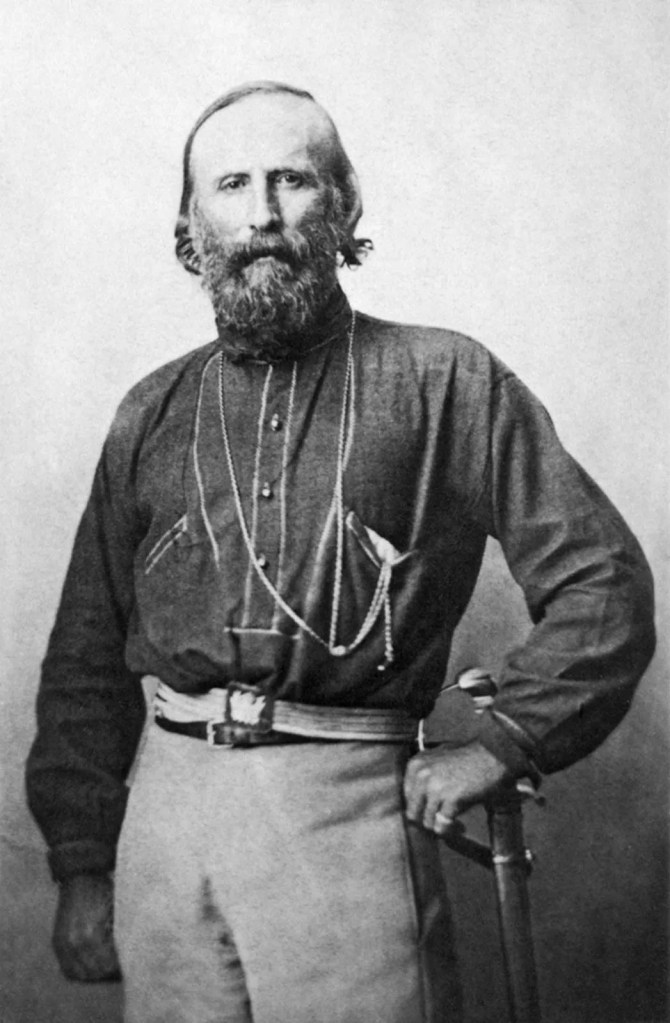

As in the rest of Europe, in Italy there were revolutionary thinkers that were fomenting such liberal aspirations. Amongst those who led these movements was Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872), who believed that liberation could be achieved by one strong and unified republican state. Then there was Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882) a follower of Mazzini. For some 30 years he repeatedly amassed voluntary militias to aid the revolutionaries to depose their autocratic governments. Another leading figure was Count Camillo Benso de Cavour (1810 -1861), who as minister to the Savoyan king of Piedmonte and Sardinia, strove for unification by extending the territory of Piedmonte, firstly by liberating Lombardy and Venetia from the Austrians. The common aim of these three important leaders was to achieve ‘Union, Liberty and Independence for all of Italy’ (D. Richards, 1977).

The earliest of the numerous uprisings occurred in 1820 – 1821, in Naples from where the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was ruled by King Ferdinand I (1816 – d. 1825), a descendant of the Spanish Bourbon dynasty. The rebellion was organised by a secret society known as the Carbonari. This uprising encouraged other similar groups, such as the Carbonari of Lombardy, to rebel against the occupying forces of Austria. However, many of the initial successes gained by these movements came to naught as the autocratic rulers were backed by the powerful Prince Metternich of Austria. Many agitators and revolutionary groups were routed, imprisoned or exiled. Others fled the country. Malta, being so geographically close to Italy was a safe haven of choice for many, more so because as a colony of Great Britain the archipelago afforded political shelter while at the same time was conveniently located for easier communication with their compatriots in Italy. Following the revolts and subsequent repressions of 1820 – 1821, one of the more notable exiles who came to Malta was the renowned poet Gabriele Rossetti (b.1783 – d.1854), a member of the Carboneria Neapolitana. After some time Rossetti moved to England where with Mazzini, he continued to help in the cause for Italian unification.

The 1830’s refugees and the Liberty of the Press

In 1830-1831, following the uprisings in Forlì, in Emilia-Romania, tens of immigrants landed in Malta (C. M. Pulverenti). Amongst them there was the prominent Mazzinian, Nicola Benzoni who sought to organise various conspiracies from Malta and subsequently took part in numerous battles in Italy. The exiles arrived at an opportune moment, when following the recommendations of the 1836 British Commission, the local governor Lietuenant General Bouverie was enacting laws to concede freedom of the press, which was granted fully in March of 1839. This concession was applicable to British subjects only, and so did not apply to the Italian refugees. However, the exiles, of whom many were men of literature or journalists, bypassed the law by collaborating with Maltese editors and printers to found their own publications in favour of their patriotic ideals. By 1840, out of 19 journals, 17 of them were run by the exiles (H. Penza, 1999). These publications were continuously being smuggled to Sicily and mainland Italy and were distributed amongst the activists of the Risorgimento. In their writings the editors featured a good dose of scathing commentaries against the autocratic regimes while inciting their compatriots in Italy to rid themselves of all political repressions. (C. Liberto, 1993).

The Mazzinian Tommaso Zauli Sajani who had arrived in Malta in 1836, founded Il Mediterraneo together with Carlo Cicognani. Many other literary writers contributed with their articles in other periodicals (M.C. Pulverini). Meantime, the British authorities were cautious of what was being published, lest any seditious, defamatory or vilifying literature was distributed whether locally or overseas. Indeed, when Lorenzo Borsini, a satirist and a journalist, attacked the local Jesuit community for its staunch anti-unionists support, and mooted that the Maltese should also stand for their rights, Governor Richard More O’Ferrall, had him deported (Angela Picca quoted by Paul Xuereb. 2018).

The Neapolitan Consul in Malta too was vigilant over the dissenting exiles and kept King, Ferdinand II (1830 – d. 1859) updated. The subversive activities of the Italian exiles were a matter of concern, so much so that on June 24, 1844, Ferdinand II, personally paid a lightning visit to Malta to discuss matters with Governor Sir Patrick Stuart. He might have been spurred to do so, following the recent arrest of the Bandiera brothers, Emilio and Attilio and 17 other companions, in Cosenza, Calabria. They were accused of their intentions to organise a military uprising against the King. The Bandiera brothers were executed by a firing squad on July 25. It was suspected that part of the subversive plans were hatched between Emilio and one of the exiles in Malta (G. Bonello, 1993).

British tolerance of the exiles in Malta

On the surface of things, the attitude of the British took a neutral stand towards the revolutionary unrest in Italy. This because, following his accession to the throne, Ferdinand II strove to distance himself from Britain. His policy was that of ‘[… a state without any intrusion from other states .…]’ and ‘[… a kingdom without a servile relationship to England …]’ (Wikipedia). On her part Britain was also concerned with the growing maritime military force that Ferdinand was raising, lest this might eventually conflict with British interests in the region. There were also various contested issues such as the use of the sulphur mines in Sicily and the ownership of Graham Island (named by the Neapolitan king, Fernandea) that in 1831 emerged from the ocean floor off the coast of Southern Sicily.

Throughout the course of the uprisings in Italy, a number of British politicians expressed their views in favour of the cause of the Risorgimento movement. Britain’s stance became clearer when in 1851, Lord William Gladstone, then a back bencher in parliament, who a year later became Chancellor of the Exchequer, and eventually Prime Minister of Britain, outright condemned King Ferdinand over the imprisonment of some 20,000 political dissenters in his realm. He described the Bourbon dynasty in Italy as ‘[… the negation of God …. erected into a system of Government …]’ (D. Richards, 1977).

About the incoming refugees, Britain kept a cautious stance. In 1850, the Governor of Malta, Richard More O’Ferrall, was instructed by Britain’s Secretary of State, Earl Grey, ‘[… not to prevent the landing of persons who may seek refuge from political motive, in any of the countries bordering the Mediterranean, provided that such persons are in a situation to comply with the law of the Island …]’, and ‘[… when foreigners arrive in large bodies they shall take up their residence at a place as you may point out to them, at a distance from the fortifications …]’ (R. Farrugia Randon, 1991).

These statements nothwithstanding, O’Ferrall, forbade on several occasions the landing of Italian refugees. He was not in favour of the unification of Italy. As an ardent Catholic he was reluctant to see Pope Pius IX deprived of the temporal powers that the papacy held over the Roman States. While in 1848, O’Ferrall had allowed 49 Jesuits to enter Malta, yet, a year later he forbade 175 Italian refugees who had sailed from Corfu, to disembark in Malta. This decision caused quite a stir in London and O’Ferrall was eventually forced to resign his post. He was replaced by William Reid, a moderate liberal (E. V. Laferla, 1938).

The Malta exiles as subversive agents

Many of the refugees were using Malta as a base where to scheme against their despotic rulers. The Neapolitan minister Prince Castelcicala complained that Mazzini in London was in collusion with the Italian immigrants in Malta. Apart from the printed material that was smuggled into Italy, an amount of weapons were also being supplied from Malta to the Italian revolutionaries. Some of these weapons were kept at the residence of the Maltese Camillo Sciberras (R. Farrugia Randon, 1991). Many refugees were willing to join the military rebels and when in 1860, Garibaldi landed with his Mille in Marsala many were those who crossed over to Sicily to join him (C. M. Pulverini).

La Primavera dei Popoli 1848

Throughout 1848, a series of revolts took place in numerous Italian states. These registered a degree of success, but eventually failed in their ultimate objectives. Such was the uprising in Palermo on January 12, whereby Ferdinand’s troops were expelled and a liberal government presided by Admiral Ruggero Settimo was installed. From Naples, King Ferdinand sent his troops to bombard Messina, – earning him the nickname ‘Re Bomba” – and by March of the following year the Bourbon troops had re-occupied the whole of Sicily. Ruggero Settimo was forced to flee to Malta where he joined many other exiles on the island.

It has been estimated that the exiles in Malta now numbered more than 1,000 – some claimed that the number was even double that (C. M. Pulverini). These immigrants looked up to Nicola Fabrizi, Pasquale Calvi and Ruggero Settimo as their leaders. However, whenever issues arose, Governor More O’Ferrall chose to communicate with Ruggero Settimo only, as he was known to be moderate and wise in his views.

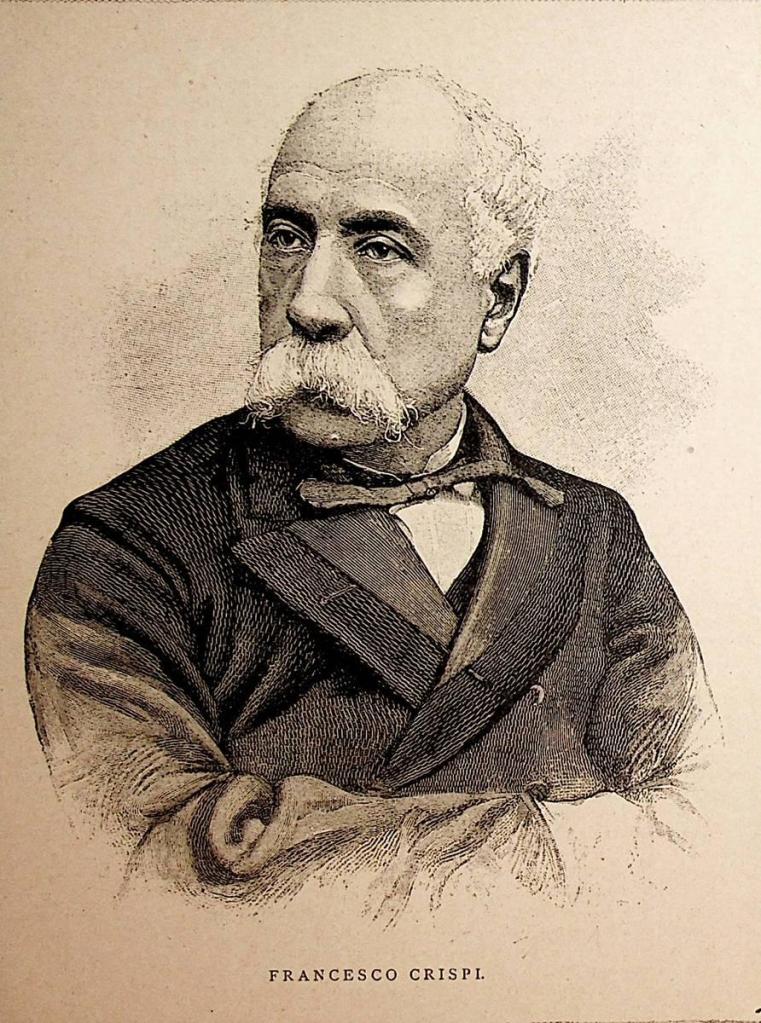

Francesco Crispi was another illustrious person who sought refuge in Malta. He fled Milan after the uprisings there and landed in Malta on March 26, 1853. He took up residence for a short while in Floriana, then in Tarxien. In Malta he published two papers, La Valigia and La Staffetta, but not for a very long time. Governor Reid took note of Crispi’s writings in which, among other things, he was inciting insurrection in Italy and vilifying the French and their Emperor. In 1854, Governor Reid banished him from Malta (G. Bonello, 2021). He was eventually elected to Prime Minister of the Italy’s unified government between 1887 – 1891 and 1893 – 1896.

Maltese attitude towards the Italian Exiles

Public opinion in Malta was split amid two different politically minded groups. There were those all out in support of the Italian cause of unification. With the arrival of the exiles in the late 1840’s, some Maltese formed the Associazione Patriotta Maltese in sympathy towards the Italian refugees. The leader of this association was Dottor Gio Carlo Grech Delicata. In the forefront there were also the brothers Emilio and Tancredi Sciberras, the sons of the Maltese 19th century patriot Camillo Sciberras. Emilio had been for a long time a very close friend of Mazzini and so he acted as his principal agent in Malta (R. Farrugia Randon, 1991).

But there were also those who saw the Risorgimento movement as an affront to the temporal powers of their Catholic and beloved Pope. These were spearheaded by Salvatore De Bono, who in 1852 became editor of L’Imparziale and L’Indipendente and later on the Portafoglio Maltese. Another powerful voice against the unification was that of the Jesuit community in Malta. These published very bitter articles against the Risorgimento movement and the local exiles’ covert activities in favour of unification.

This two pronged stance of the Maltese was openly manifested when on 23rd March 1864, General Giuseppe Garibaldi landed in Malta for a couple of days, prior to boarding a British ship to travel to England. He lodged at the Imperial Hotel in Strada Santa Lucia, Valletta. Many Maltese liberals paid him homage. The Corriere Mercantile Maltese and the United Services Gazette hailed the Italian as a hero in their eulogies. On behalf of the Associazione Patriottica, Baroness Testaferata Abela read out to him a short address signed by some 300 Maltese, calling him ‘the leading man of the century’. Not so the Salvatore De Bono’s Portafoglio Maltese which branded Garibaldi as the enemy of the Church and its Pope. Moreover, some Maltese booed Garibaldi whenever he appeared in the window of his hotel. On their side, the British revered Garibaldi for his deeds. Thus, when he was about to sail from Marsamxett Harbour, soldiers of the 25 regiment were positioned in line on Fort Manoel to give him ‘repeated cheers of farewell’. (J.A. Filletti, 1974).

Post Unification

As from the days when the new Italian constitutional monarchy was installed in Turin under Vittorio Emanuele II, King of Piedmont and Sardinia, a fresh wave of refugees, this time loyalists of the ancien regime, landed in Malta. Following Garibaldi’s capture of Palermo in 1860, he proscribed the Jesuits to be exiled and these sought refuge in Malta. They were eventually allowed to open a college in Gozo (E.V. Laferla, 1938).

Now that the coin had been reversed, the newly born Italian unification government, was concerned with the presence of the Italian loyalists in Malta. The newly appointed Piedmontese Consul to Malta, kept an eye on the local situation. Similar to what happened before with the Italian revolutionaries, the new exiles also produced their own propaganda material to be shipped clandestinely to Sicily. Hostility towards the Italian government was not provided by pen alone but also by the provision of weapons and gunpowder that was smuggled into Italy from Malta.

In the late sixties and early seventies, especially after the French, defenders of the Papacy were called back to France to face the military threat from Prussia, the unification government took complete control over Rome. This is when the loyalists in Malta saw that their cause to prop back their rulers into power was no longer tenable and so many of them settled down for a more peaceful life, most of them in the Maltese islands.

Conclusion

The Risorgimento movement, and eventually the arrival of the new exiles, certainly influenced in many ways the educated classes of Maltese society. Indeed, with their writings the Italian exiles may have well sown the first seeds in the minds of the those politically active that awakened a desire to have a meaningful say in local politics, although nothing close to a liberation from Britain. In literature, the 19th century Maltese writers of novels, poems and drama imbibed a lot from the Italian exiles regards to style and choice of subject matter (A. Cassola and J. Muscat, 2023). Another profound effect was the infusion of a greater interest in Italian culture on all levels including the the inclusion of a quantity of Italian terms and expressions in the Maltese language.

SIGNIFICANT DATES

1820 Revolt by the Carbonari in Naples.

1830 – 1831 Revolts in Forli .

1839 Introduction of the liberty of the press in Malta

1848 Revolts in Italy. Mazzini headed for a short period a Republican government in Rome.

1856 Another revolt in Sicily.

1859 Revolts in Modena, Parma and Tuscany – their dukes exiled. Revolt in Romagna, one of the Papal States.

1860, Garibaldi and his Mille land at Marsala, captured Palermo and eventually all of Sicily except Messina.

1861 A new parliament met in Turin headed an almost unified Italy. Victor Emmanuel becomes king.

1864 Napoleon III withdrew his troops from Rome.

1866 The Piedmontese troops entered Venice.

1870 Once again, Napoleon III abandoned Rome thus bringing final unification all over the Italian peninsula.

© Martin Morana

19 March, 2024

Bibliography

Bezzina Joseph, ‘Asylum in Malta – A British offer to Pope Pius IX’, The Sunday Times, April 15, 1990.

Bonello Giovanni, ‘Francesco Crispi – A turbulent future prime minister expelled’, The Sunday Times of Malta, February 14, 2021.

Bonello Giovanni, ‘King Bomba’s mysterious Malta visit’, The Sunday Times, July 25, 1993.

Cassola Arnold, ‘Italo-Maltese relations c. 1150 – 1936’ – People, Culture, Literature, Language’.Mediterranean Review, Vol. 5, No. 1. June, 2012.

Clements Richard, The British and the Risorgimento’, History Review, December 1999.

Facineroso Alessia, ‘The Sicilian Revolution of 1848 as seen from Malta. Symposia Melitensia. 2010, Vol.6.

Farrugia Randon R., Camillo Sciberras – His Life and Times. Gutenberg Press, 1991.

Filetti J.A., ‘Important Visitors to Malta – Giuseppe Garibaldi’, Heritage Encyclopedia, Vol IV. (1974).

Grima Joseph F., ‘The Printing Press in Malta Under the British (1836 – 1839), Heritage Encycopedia. Midsea Books Ltd. 1979.

Grima Joseph F., ‘Garibaldi’s visit to Malta’, Kultura and Times of Malta (no date available.

Ganado Herbert, Rajt Malta Tinbidel Vol I.

Laferla A.V., British Malta, Vol I. A.C. Aquilina & Co. 1976.

Liberto Carlo , Siciliani Illustri a Malta. Publishers Enterprises Group Ltd. 1992.

Mercieca Simon, ed., Mazini and Malta Italian – Proceedings of History Week, 2005. Malta Historical Society. 2007.

Mizzi John A., ‘When Malta was offered as a refuge to Blessed Pius IX’, The Sunday Times, October 1, 2000.

Muscat Jake, ‘The Echo of the Risorgimento’, The Malta Independent, 19th March, 2023,

Penza Herbert, ‘IL GIURNAL MALTI u l-Isfond Storiku Kulturali ta’ Żmienu’ Dissertation, Faculty of Eductation, University of Malta. May 1999.

Pulvirenti Chiara Maria, ‘Un Asilo Mediterraneo lungo il Risorgimento Malta, la libertà di stampa, l’esilio’. École française de Rome. (internet source, no date supplied).

Richards Denis, An Illustrated History of Modern Europe, 1789 – 1974. Longman. 1977.

Xuereb Paul, ‘Malta A refuge for Italian Exiles’. The Times of Malta, May 20, 2018. A review of Angela Picca’s ‘Pugliesi per l’Italia Unita, dalla Rivoluzione Partenopea (1799) a Porta Pia (1870)’.

Zarb Dimech Anthony, ‘The Italian Risorgimento and Malta’ The Malta Independent, 11th October, 2022.

Publications by the same author …. please click here :

Il-jum it-tajjeb sur Morana. Irċevejt b’imejl l-artiklu dwar l-eżiljati tar-Risorġiment Taljan u xtaqt inżid xi ħaġa fil-qosor. Eżiljat ieħor li kien ħarab lejn Malta u kien ġie joqgħod f’Bormla kien Giovanni Ricci Gramitto li kien jiġi missier Caterina, omm id-drammaturgu famuż Taljan Luigi Pirandello. Jiġifieri Giovanni Ricci Gramitto kien jiġi in-nannu matern ta’ Pirandello. Giovanni kien wasal Malta fid-29 t’April tal-1849 fuq it-tartana Nettuno. Fit-18 ta’ Ġunju tal-istess sena flimkien ma’ ibnu Francesco kien mar jilqa lil kumplament tal-familja li kienu martu u s-sittb uliedhom l-oħrajn – tlett bniet u tlett subien. Caterina kien għad kellha tlettax il-sena. Giovanni Ricci Gramitto miet f’Bormla (fejn għad hemm il-kitba tal-mewt tiegħu fil-parroċċa) fl-1 t’Awwissu tas-sena 1850 fl-eta’ ta’ 46 sena x’aktarx bil-marda tas-sider. Indifen fil-knisja tal-kappuċċibi fil-Kalkara li dak iż-żmien kienet tagħmel mal-Birgu. Din il-ġrajja Luigi Pirandello kien daħħalha fil-ktieb ‘I Vecchi e i Giovani’ li fih tissemma Burmula u fih jagħmel użu minn deskrizzjonijiet ta’ ommu dwar Bormla huma u deħlin fuq it-tartana Emilia waqt li wkoll ħoloq karattri msawrin minn eżiljati li kienu jgħixu f’Malta. Dwar dan kollu kont ktibt artiklu, ovvjamnet ferm iktar detteljat fil-gazzetta It-Torċa tat-23 u t-30 ta’ Diċembru 2012. Grazzi u saħħiet

LikeLike

Grazzi ħafna Dione tal-informazzjoni… interessanti ħafna li qiegħed tinfurmani bih int …. Din l-informazzjoni ser inżomma u nfittex aktar fuqha …. Insellimlek.

LikeLike