The Sette Giugno Affair

Introduction

The riots that took place in Valletta and in elsewhere in Malta, on June 7 and June 8, 1919, did not occur in isolation. The riots were the result of so many frustrations amongst the Maltese, that had pent up since decades earlier. Throughout the whole of the British period, starting from the early 1800’s, the economy of the Maltese islands bloomed and withered according to how much the British invested in Malta on military projects and according to the presence of the Royal Navy in Maltese ports.

Throughout the first two decades of the 20th century, discontent was felt among all stratas of society. The demands by workers for better wages were simply ignored by the British administration. The Police, then some 500 in all, had been awaiting a revision of their pay since 1905 (E. Attard, 1999). The Post Office workers and teachers were also making similar demands. Discrepancies existed between the wages of Maltese employees and their British counterparts doing the same job, the British personnel always receiving a more advantageous pay (M. Sant, 1989).

Political unrest throughout the early decades of the 20th century

The ‘Knutsford Constitution’ by which the Legislative Council headed by the Governor had functioned since it was established in 1887, had been revoked in 1903, following a series of never ending disputes amongst the Council members and especially in confrontation with Lord Gerald Strickland, then Chief Secretary to the Governor of Malta. The main issues were over money matters and the ‘pari passu’ principle as opposed to the ‘freedom of choice’ in schools for children wanting to learn English or Italian. Matters came to a head and Governor Grenfell could take it no more. On advice of Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the started vetoing all legislative issues by Orders-in-Council and thereafter he abrogated the 1887 Constitution. London then imposed a new constitution, whereby the elected members became a minority – 8, as opposed to 12 official members. This was unacceptable to the elected Council members and they resorted to abstentionism for most of the next sixteen years. This gave the Governor leeway to administer the country solely aided by his Executive Council.

In such a political moratorium, in 1905, Filippo Sciberras, a Maltese medical doctor who like his ancestor Camillo Sciberras, bore great patriotic sentiments, together with Fortunato Mizzi and the cleric Panzavecchia formed the Associazione Politica Maltese a non-partisan committee. The principal aim of the association was to attack the legitimacy of the Government and seek, through popular support, a fresh and liberal constitution. (Robert Farrugia Randon, 1993 & 1994). Yet the political aspirations of the Maltese were to languish in limbo for many years to come.

World War I – a mainspring for the Sette Giugno riots

As from 1914 onwards, while the battles fought were distant from Malta, the shifting of troops certainly boosted the local economy. Each month, some 800 ships from various nations were calling at Malta’s ports. (A.V. Laferla, 1977). Many of these needed bunkering as well as other ancillary services. Maltese soldiers and hundreds of unemployed, enlisted to join the troops to earn some cash, even if this meant putting their lives in danger. The Dockyard was in overdrive mode and its workforce soon rose from 5,000 to 12,000. Apart from this, 27 hospitals were set up to tend to the wounded and the sick, returning from the battlefronts.

However, the same war also brought about a lack of basic essentials such as wheat, which now was imported all the way from Australia, instead of from Odessa or Egypt as it used to. The flour was often mixed with potato or rice and the taste was awful. Fuel, needed to light up kitchen stoves was also scarce. This situation was brought about by the fact that merchantmen carrying such commodities were being targeted by German submarines (M. Sant, 1989). Another reason for the scarcity of such essentials was the hoarding of foodstuffs and other provisions. Thus, the price of bread, a staple for the Maltese, shot up threefold; from 2½ pence per rotolo in 1914, to 7½ pence per rotolo by 1918 (C. Galea Scannura, 1979). This hike in prices was also compunded by high inflation.

Throughout the war years, as the work in the Dockyard increased, so where the resentment brought about by the conditions of work. In 1916, instigated by the teachings of Manwel Dimech, many workers joined the Malta Government Workers Union (M. Sant & M. Montebello, 2019). In May 1917 some 10,000 workers went on a seven day strike. This followed the completion of 25 flying boats. When the workers were offered a 10% bonus for their work these felt that they were being short-changed (J. Bonnici & M. Cassar, 2004). According to Laferla, ‘the Dockyard worker became aware of the importance of his work and had gained self-respect, at a time when due to the inflation not even a prison diet was procurable’ (A.V. Laferla, 1977). Taking the cue from the Dockyard workers, the police also went on strike, in October 1918. (H. Frendo, 1979).

In 1918, the Executive Council introduced new tax legislations. The two laws were the Stamp Duty Ordinance and the Succession and Donation Ordinance. This law irked the Maltese middle class. Moreover, it also vexed the local Church, then the largest recipient of property, inherited mostly by benefices. The Curia protested vehemently and the British backtracked and exempted the Church from taxation. This brought about the indignation of the anti-clerics, many being stalwart members of Manwel Dimech’s Xirka tal-Imdawlin. They considered this act as tangible proof of collusion between Bishop Mauro Caruana, an Anglophile, and the State, to the detriment of the proletariat. This anti-clericalism can also be evidenced by a plot that was discovered that some instigators had threatened to blow up the bishop’s residence with dynamite Fabian Mangion, 2019).

Post war discontent leading to the Sette Giugno riots

Once the Great War came to an end in November 1918, a huge amount of Dockyard workers were set to be released. By mid-March of 1919, a few hundreds were laid off. By September, some 8,800 were struck off the Dockyard’s labour force. To rub salt to the wound, Malta, as the rest of the world was hit hard by the Spanish flue pandemic which caused the death of some 830 people. The future was bleak and emigration was hardly an option, as America was no longer accepting immigrants who were illiterate (A.V. Laferla, 1977). Apart from these matters, discontent thrived on false rumours; one such rumour was that the rise in flour was due to the government levying a war contribution from the sale of flour. The opposite was actually the case as authorities in London were advocating the lowering of Maltese financial contributions.

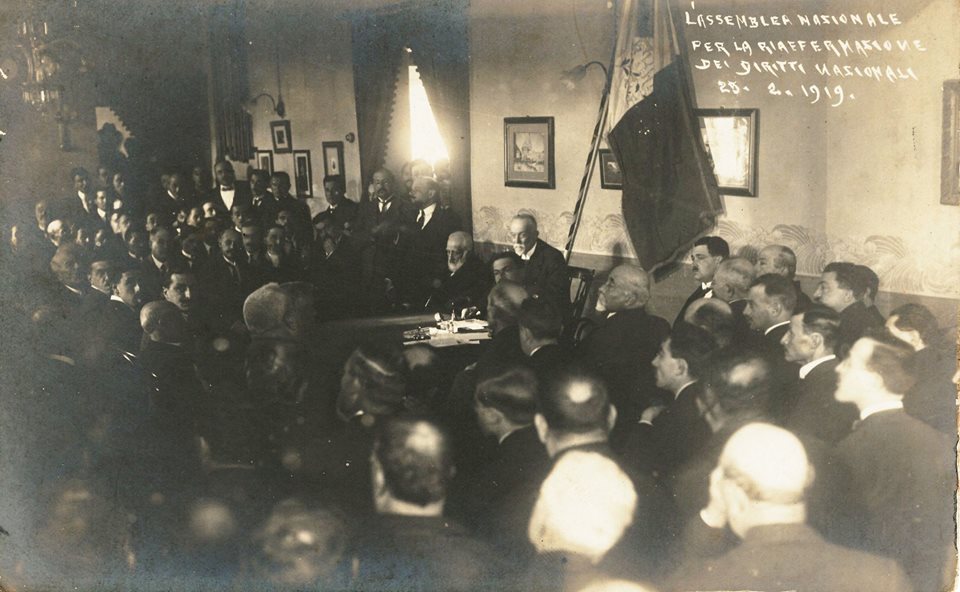

The Big War over, Dr. Filippo Sciberras as a leading member of the Associazone Patriotica Maltese, thought that the time had come to cut the chase. Thus, in November 23, 1918, through the gazette Malta, he invited interested parties – be they individuals or groups – to meet up in order to form an Assemblea Nazionale to set the ball rolling and draft a constitution that would be presented to the authorities in London. The first meeting of the assembly was held in Valletta on February 25, 1919, at the Circolo La Giovine Malta in Strada Reale corner with Strada Santa Lucia. While that first meeting was being held, the University students took to the streets to air their grievances against the proposed changes in the way their courses their graduation was being arbitrarily delayed (J. Bonnici & M. Cassar, 2004). This disturbance may have been a harbinger of the riots that were to take place on June 7.

‘Tear down the Union Jack with its Maltese flag’

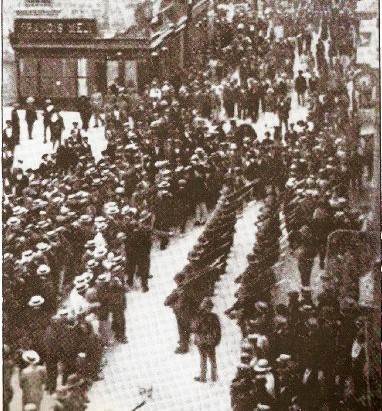

The Assemblea Nazionale held its second meeting on Saturday, 7 June, in the afternoon, at the same premises. The members of the assembly had urged one and all to enter the capital to demonstrate their solidarity towards her. By 4.30 pm, a crowd of some 3,000 had gathered in Strada Reale. Those present included hundreds of supporters of Enrico Mizzi’s Partito Nazionale; also present were the Dockyard workers and the University students. Soon, amongst the crowd one could discern a palpable anti-British sentiment.

When the crowd moved down Strada Reale to reach Strada San Giovanni a British flag hoisted on the shop A La Ville de Londre, was spotted that together with the Union Jack bore also the Maltese colours. On the spur of the moment, a number of those present busted the door of the shop in, entered the premises and tore the flag down, mast and all.

It just happened that on that day, many government buildings also had the British flag flying, albeit at half mast, as a sign of respect following the passing away of Chief Justice Sir Vincent Frendo Azzopardi. Thus, when the crowd got wind of this, part of the demonstrators splintered off towards those buildings to repeat the same motions.

Then, the angry mob converged onto Piazza San Giorgio, (Palace Square) and headed towards the premises of the Daily Malta Chronicle, located next to the Casino Maltese in Strada Teatro. This newspaper was pro-British and when the Dockyard workers had gone on strike in May of 1918, its editor, Augusto Bartolo, had not shown any sympathy towards them. (H. Ganado, 1977). The mob forced its way into the building ransacking and setting on fire all that they could lay their hands on.

Then, a section of the crowd headed to Strada Santa Lucia and downhill towards the Marsamxett side to carry out similar acts of vandalism on the residence of Francesco Azzopardi, a politician who, more often than not, did not follow the boycotting of the Council and so was very much disliked by the public. His residence was broken into and furniture was thrown into the street below. Apzzopardi had to seek shelter within army barracks and later was spirited away together with his son to Egypt until things quietened down (M. Sant, 1989).

Then the crowd-turned-mob headed to Strada Forni, close to the Augustinian Church, to attacked the residence of the entrepreneur Cassar Torreggiani, an importer of wheat and the appointed president of the Chamber of Commerce. He had also been, during the war years, president of the Price Control Board. The angry crowd broke the front door down and proceeded to do the same as they did to Azzopardi’s residence.

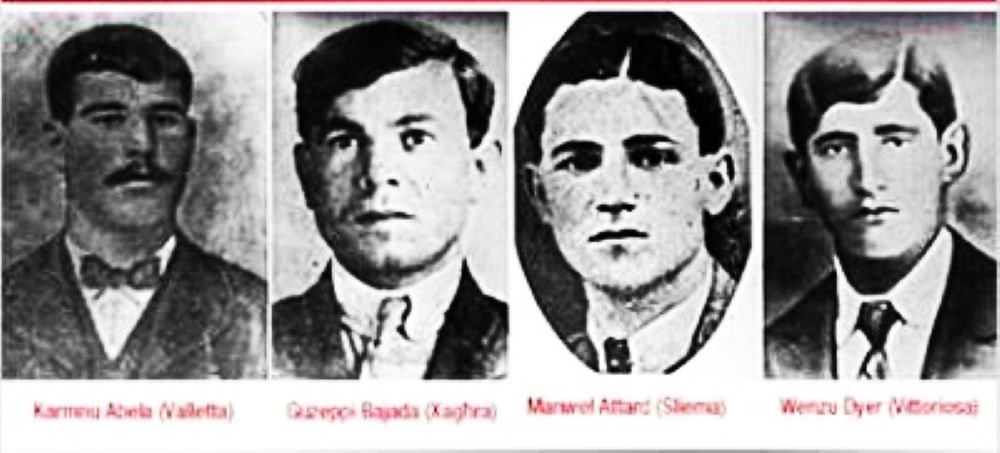

Against this rampage, the police – some 180 were deployed, did next to nothing to quell the troubles. One must also state that they were unarmed and felt helpless against the angry demonstrators. At around 5.30 pm, Lieutenant Governor General Robertson, who was filling in the post of governor, following the departure in April of Lord, ordered some 70 soldiers to march to Strada Reale. From near the law courts the soldiers were then split into penny packets to protect the buildings under attack. Sure enough, in such small units these were not able to show any command of the situation. Perhaps in fear of their lives the soldiers guarding the residence of Cassar Torreggiani fired at the threatening mob, apparently without orders from their superiors. Consequently several were injured and two men were shot dead. These were Manwel Attard, 26, a barber from Sliema and Ġużè Bajada a 38 year old from Xagħra.

Meantime, a few soldiers had gone to the Daily Malta Chronicle and entered the premises to check on possible gas leaks. When they were about to exit the building, the soldiers came face to face with an agitated mob outside. Shots were fired and at least two persons were hit, one of them Wenzu Dyer, a 19 year old dockyard worker from Birgu. Dyer staggered a few meters and then fell dead. The British soldiers’ intervention on that day had wounded many and shot three dead.

Violence continues on Sunday

Early Sunday morning, June 8, many entered Valletta once more. However, Herbert Ganado says that the crowd on Sunday was made up of a different element, many were roughnecks (H. Ganado, 1976) and some were armed with pocket knives (H. Frendo, 2019). At 9.30 in Strada Teatro, a British soldier was set upon, and was left senseless on the ground. He died one month later (M. Sant, 1989). Part of the crowd approached once again the building of the Daily Malta Chronicle and set the furniture on fire. The members of the Casino Maltese were jeered and soon the door of the club was closed. Then a sizeable crowd moved towards the Union Club, further down the road (today’s Archaeology Museum). The Union Club was then an exclusive one reserved for the local British military officers and other elite. It is said that at that moment those inside the building insulted the crowd by throwing pennies at them from the balcony. The marines were sent there to disperse the crowd forthwith. The demonstrations and disturbances in Valletta and elsewhere continued on and off throughout the day.

Then, at around 6 pm a number of malefactors turned their attention to the Francia residence located in Strada Reale, in front of the Royal Opera House. Like Cassar Torreggiani, Colonel Francia was an importer of wheat, and so, in the eyes of many, he was also to blame for the high price and the quality of the bread. Many assaulted his residence from a side door in Strada del Fianco (today Ordnance Street) and ransacked the house, throwing furniture into the inner courtyard. By then, the Francia family had locked itself in the cellar to escape the wrath of the agitated mob. At around 7 pm, some 250 soldiers of the Royal Malta Artillery were dispatched to clear the place and Strada Reale but did little to disperse the crowd. When it had become obvious that the Maltese contingent was ineffective, a group of 140 British marines, that were at the time posted near the Customs House were deployed. These marched up to the Francia residence. On arrival they found the mob still pillaging the house. According to the popular narrative, Carmelo Abela, 38, was present simply as a bystander, seeking to locate his son whom he believed to be with others inside the house. The marines tried to arrest him but he resisted and was bayonetted and mortally wounded (M. Sant, 1989). Abela died of his wounds nine days later, on June 16. However, it is curious to note that in an official list of the wounded and killed, it is clearly stated that Abela was bayonetted when inside the Francia residence. The same document also states that eight others were also bayonnetted and injured by the marines at the same location.

Apart from these four victims, historians maintain that during the riots there where three others who died later on as a result complications to their injuries. Prof. R. Mangion mentions Francesco Darmanin, Federigo Brogdorrf and Antonio Cassano. The latter was actually injured when he fell and broke a leg and died later of complications. He was 77 years old. (R. Mangion, 2019).

Apart from the disturbances in Valletta, other violent acts took place elsewhere in Malta. On that same Sunday, at around 8 pm, at Ħamrun, the mill and residence of ‘is-Sur Luigi Farrugia’, was attacked by a crowd of several hundred men. The same happened to the mills owned by Cassar Torreggiani in Marsa.

Post Sette Giugno

Many believe that the above incidents put the demands for a Responsible Government and for a liberal constitution on a fast forward motion in order to establish a long term solution to the major ailments of the population. Others believe that the granting of a liberal constitution had already been promised to the Assemblea Nazionale by the Colonial Minister Lord Milner in May and so the riots were unecessary (H. Frendo, 1979). But how can you explain to a jobless bread-winner that he needs to wait for a fresh and liberal constitution? Weeks prior to the Valletta. meeting thousands of Dockyard workers were given the sack. The Sette Giugno riots served as a rude wake-up call for the British authorities. Certainly, the new governor, Lord Herbert Plumer who arrived in Malta on Tuesday 10 June, took the bull by the horns and did everything in his power to avoid a repeat of the violent acts.

In August of 1919, the National Assembly presided by Filippo Sciberras met again, this time at Lia. The Assembly voted for a final draft of the constitution to be sent to London to the parliamentary under secretary of state for the colonies, Leopold Amery. The new constitution provided for the setting up of a Legislative Council that would consist of two Houses, a Senate and a Chamber of Deputies. Eventually the omonimous constitution was approved. In October 1921 national elections were held to elect a new autonomous parliament. On November 1, 1921, the new Legislature was inaugurated by the Prince of Wales.

© Martin Morana

7th June 2024

* * *

Biblijografija

Attard Eddie, ‘80th anniversary of June 7 riots – The police in the 1919, riots and their aftermath’, The Sunday Times, June 8, 1999.

Attard Eddie, ‘The Police and the June 1919 events’, The Sunday Times of Malta, May 26 & June 2, 2019.

Blouet Brian, The Story of Malta. Progress Press Co. Ltd. 1981.

Cassar Michael & Bonnici Joseph, Chronicles of Twentieth Century Malta. Book Distributors Ltd. 2004.

Farrugia Randon Robert, Sir Filippo Sciberras, His Life and Times, 1994.

Farrugia Randon Robert, ‘Towards Responsible Government – Historical Background of Constitutional Developments Up To 1921’. Mid-Med Bank Annual Report, 1993 (?)

Fenech Dominic, 1921 – Self Government in Malta 1921 -1933. Midsea Books, 1921.

Frendo Henry, Politics in a Fortress-Colony – The Maltese Experience. Midsea Publications. 1979.

Galea Michael, The Sette Giugno Riots – A post script’. The Sunday Times, June 2, 1998.

Galea Scannura Carmel, ‘The Sette Giugno Affair’, Heritage Encyclopedia, Vol. 1. Midsea Books Ltd. 1979.

Ganado Herbert, Rajt Malta Tinbidel – L-ewwel Ktieb, 1900 – 1933. Interprint Ltd. 1977.

Laferla A.V., British Malta, Vol II. A.C. Aquilina & Co. 1977.

Mangion Fabian, ‘Mgr Joseph Depiro: a sincere and genuine patriot’, The Sunday Times of Malta, June 2, 2019.

Sant Michael, ‘Sette Giugno’ 1919 – Tqanqil u Tibdil. Sensiela Kotba Soċjalisti. 1989.

Zarb-Dimech Anthony, Malta during the First World War, 1914-1918. Veritas Press. 2004.

Seminar at University Class: ‘The Sette Giugno Riots’ (various participants). 28th November 1988.

Mitt Sena mis-Sette Giugno – Anniversarju 1919 – 2019. (Artikli minn awturi diversi). Union Print. 2019.

More articles may on various topics of Maltese history and culture may be read on the same website. One may also be interested to read other publications by the same author by clicking here: