A * B * Ċ * C * D * E * F *

Ġ * G * GĦ * H * Ħ * I * J * K *

L * M * N * O * P * Q * R * S *

T * U * V * W * X * Ż *

THE MALTESE MAXRABIJA

The mashrabiya of the Arab world

The term mashrabiya refers to that balcony often found in the Arab world and beyond, that takes the form of a large wooden latticed box attached to the facade of a building. The lattice screen is intended to protect the facade and the room behind it from the harsh rays of the sun. The mashrabiya is located on the first floor of the building or higher, thus commanding a view of the immediate surroundings. Some scholars maintain that this wooden structure originated during mediaeval times. According to hearsay, in the Muslim world, this balcony may have well served to conceal the women of the house from the public eye.

So much for hearsay. If one were to delve into the etymology of the word one will become aware that the word mashrabiya is a misnomer as it really refers to something completely different. The word probably derives from the verb شرب shuriba, (he drank). From the roots of this verb, sh – r – b, the verbal noun mashrabiya was coined to refer, possibly, to a particular spot in the house where containers holding water, milk or any other beverages, were stored. In Arab countries, where temperatures are constantly high all the year round, a cool storage place was necessary so that liquids or food stuff were kept. This storage place might have been located in a corner furthermost from the outside heat and possibly close to a ventilation shaft or aperture where temperature was somewhat cooler. Hence the word mashrabiya, as a cooling place for liquids.

Another term for the lattice balcony is often used in the Arab language, namely, mashrafiya. In Arabic, the word shurfatun شرفة from which mashrafiya is derived means, a balcony or veranda. Related to this word, in the Maltese language there is the word xiref / tixref, which means to lean forward in order to look outside, as when saying, ‘tixref mit-tieqa’ to peer out of a window.

The Maltese maxrabija

Curiously enough, the term maxrabija / muxrabija does not feature in any of the two comprehensive, 18th century dictionaries, namely, the Damma of Agius de Soldanis and the Lexicon of Mikiel Anton Vassalli (1796). Neither is it included in Vincenzo Busuttil’s Maltese – English Dictionary (1900). It is as if the word that was applied to the Maltese maxrabija was coined in recent times.

In his brief exposé of the Maltese maxrabija, Carol Jaccarini provides alternative terms by which the box like structure was / is referred to, such as, rewwieħa, xerriefa, nemmiesa, kixxifija, glusija (C. Jaccarini, 2004). The latter term, compares the function of the maxrabija to that of a glusa. This is a nautical term meaning, falk or bulwark. Indeed the maxrabija fronting the aperture, acts as a protective screen that prevents the rain water from reaching the interior of the aperture. (See: J. Aquilina’s Maltese English dictionary, (1987), and J. Caruana’s Termini Nawtiċi (2019). The first term mentioned by Jaccarini, rewwieħa, means a ventilator. The other terms mentioned are related to the verb, ‘to observe’ or ‘to spy’.

In the Maltese context the name maxrabija refers always to that screen placed over an aperture in the walls of houses. In spite of the remote resemblance to the Arab masharabiya, this feature is in all probability of purely local origin. No ancient architectural remnants or written documentation have survived to show that the Maltese maxrabija is in any way historically connected to the Arab balcony. To my knowledge, neither the Arab mashrabiya nor the Maltese maxrabija have ever been traced to Muslim Sicily, whereat the Arabs who conquered Malta in 870 AD, came from.

The main features of the maxrabiji

In his detailed survey of the Maltese maxrabiji, Joe Azzopardi states that at present, in the Maltese islands, there are 15 stone maxrabiji and 35 that are made out of wood. Twenty one other maxrabiji that were documented have not survived (J. Azzopardi, 2012). Most of the maxrabiji are located on the front side of buildings, mostly on private residences. They are defined mainly by the perforated screens. Bar very few exceptions, the maxrabiji do not contain any refined ornamental work. The screen covering the porthole inside the wall is often drilled on each side including the bottom ledge. It is these holes that inspired the imagination of many to claim that the Maltese maxrabiji were meant to serve as a watch-out post of sorts. By such a device the resident of the house would be able to espy onto the street below, without him or her being seen.

The maxrabiji vary in their shape and size. There are vertically mounted maxrabiji as well as horizontally positioned ones. The vertical boxes have an average height of around 50 – 60 centimetres and are between 30 or 40 centimetres wide. The horizontal ones have roughly the same measurements, but the taller measurements become horizontal. Most maxrabiji jut outward from the wall, from as little as a few centimetres up to some 30 centimetres.

The stone maxrabija

The reason why the maxrabiji were made of stone may be too obvious. Stone is the only building material found in profusion on the Maltese islands. It was also the preferred material for the maxrabija because it could withstand the elements better than wood. The structure could be mortised into the stone wall and no maintenance work was required. Many of the stone maxrabiji are made of different slabs fitted together, but sometimes they are carved out of one single stone. Some of the maxrabiji have an oblong screen, others slanting and a few are polygonally shaped.

The so called spy holes that often dot each maxrabija screen are often drilled in the shape of narrow slits or holes. Of the known stone maxrabiji, only one has a screen made up of a series of louvered slits. This is located on a house front in Triq il-Muxrabija in Għasri, Gozo.

The wooden maxrabija and its spy holes

It is assumed that the wooden maxrabiji were produced at a later time when wood became more available locally and therefore was easier and cheaper to acquire. During the time when the Order of St John ruled Malta, as well as during the early years of the British period, wood was often imported to be used for the construction or maintenance of sea faring vessels. Thus, to the Maltese craftsmen there was now available a durable material, such as red deal wood which would withstand the weathering. The screens are sometimes covered in lattice work, others have louvers (similar to the persjani shutters of windows). These were meant to allow air to draught in and out of the aperture while at the same time protect the same aperture and the interior of the room from direct sunlight or rain.

The historical use of the maxrabija

In earlier centuries, edifices, especially private residences barely had windows on their front or side walls. A window was perceived as an aperture that would weaken the protective qualities of the outer walls of the residence. Walking through many ancient village cores one will often notice that old windows are often small and secured by iron bars either in the shape of a grill or else iron bars in the shape of a cross. The lack of windows on the outside was made up for on the inside, as the rooms, more often than not, were positioned so that one side would abut a courtyard. It was from here that rooms could receive sunlight and be kept fresh by opening windows that overlooked the courtyard. If the rooms lacked fresh air, then a ventilator could be opened on the wall that touches the exterior of the house.

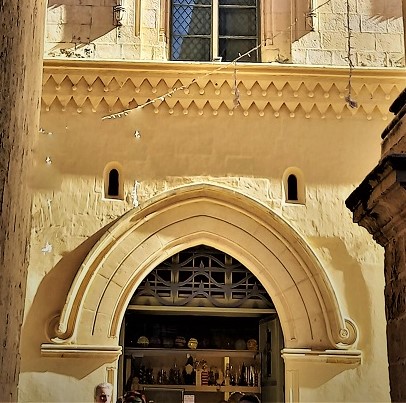

The case of Palazzo Falson

An example of ancient small apertures on the outside wall may be seen on the facade of Palazzo Falson, in Mdina. On the ground level, just above the left entrance one will observe two chinks cutting through the facade. These small oblong holes contrast sharply, by their austere and inconspicuous qualities with the ornate windows that are on the floor above. The windows on the first floor were crafted some time in the early 16th century, the small apertures on the ground floor are more ancient. One wonders why these portholes are not protected by iron bars at least. One may therefore reason that these were covered by a screen similar to those of the maxrabija. In such a major passageway as that in the then capital town of Malta, frequented as it was by a dense population, the residents inside the Palazzo would certainly not feel secure if such apertures, so close to the street level, were left exposed.

The gwardakarne

Some of the still extant maxrabiji defy the purpose of the stereotyped spy holded screens, in that they do not contain a wooden screen at all. Instead they have wire meshing or else glass panes (see Joe Azzopardi, 2012). In this instance, the purpose of the maxrabija to provide a shaded and ventilated aperture in the wall must have been abandoned in recent times. The wire-meshed windows provide a close resemblance to the gwardakarne, which in olden times was used by many families to store salted meats such as sausages for these to cure. The gwardakarne was often part of the kitchen furniture, hung at a certain height from the floor, at level with a window from where a good breeze could draught.

Further investigation is required

In order to define the real purpose of the maxrabija, it will never be enough to admire these appendages from outside. It is necessary to inspect each and every one from the inside of the room where they are located. Most muxrabiji are located on the higher stone courses of either the ground floor, or else on the second floor. Joe Azzopardi states that some are located somewhere along the steps leading up from the ground floor to the first. One must check on their interior height where they are located in order to understand their accessibility and therefore their utility.

And what about the supposition that the maxrabija was used as a spyhole? Here one should take into consideration the thickness of the wall behind the maxrabija. If the wall is double layered (ħajt dobblu), and if the aperture inside the wall is not large enough to allow head and shoulder to lean into the aperture, then it would be impossible to reach the box outside to be able to gain a good view of the street below because the spy holes would be too far away to reach.

Conclusion

There may have been a variety of reasons why the Maltese maxrabija was included in the Maltese buildings . To my mind, Robert Galea, in his article, ‘The Muxrabija – Window’ (2009), succinctly sums up the general usefulness of the muxrabija by the following argument, ‘[…] Security, privacy and climatic factors, seem to have favoured bleak facades with a minimum of openings, and it seems that the muxrabija-window was one of the resultant features […]’.

———

Post scriptum

The thousands of ventilation shafts, located as they are at the topmost corner of rooms touching the outer walls of houses, may act as a faint reminder of the maxrabija of old.

© Martin Morana

08. 06. 2023

Bibliography

Azzopardi Joe, ‘A Survey of the Maltese Muxrabijiet’, Part one and Part two. Vigilo, April 2012, no 41; Vigilo, October 2012. Din L-Art Ħelwa.

Caruana Joseph, Termini Nawtiċi. BDL. 2019.

Jaccarini Carol, ‘Il-Muxrabija, Wirt l-Islam fil-Gżejjer Maltin’, Folklor – Ġabra ta’ kitba minn membri ta’ L-Għaqda Maltija tal-Folklor, Ed. Guido Lanfranco. Klabb Kotba Maltin, 2003.

Galea Robert, ‘Il-Muxrabija Window’, Treasures of Malta No 44, Easter Vol XV, nu.2, 2009.

https://www.abiya.ae/knowledge-nehal/history-of-mashrabiya

Pubblikazzjonijiet tal-istess awtur – ikklikkja hawn: https://kliemustorja.com/informazzjoni-dwar-pubblikazzjonijiet-ohra-tal-istess-awtur/